Contributed by Laurie Fendrich / Singling out individual works for praise in an exhibition of the size and range of MoMAs Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction is almost beside the point. Her first US retrospective in 40 years, it includes 300 of her approximately 1,200 extant works: pencil drawings, gouache drawings, oil paintings, murals, painted reliefs, wool tapestries, rugs, pillows, embroidered lace, tablecloths, glass-beaded jewelry, womens handbags, sculpture and sculptural objects, masks, costumes, puppets, graphic design, set design, stained glass windows, furniture, and examples of her interior and architectural designs. And tagging Taeuber-Arp (18891943) multidisciplinary, as MoMA duly does, doesnt begin to describe this nonpareil artist. During her Dada years, she also studied and performed modern dance, taught applied arts, and wrote numerous essays on art. She believed human beings possess a deep-seated compulsion to physically beautify all the things around them, and thats precisely what she tried to do in making everything from paintings to purses. To imaginatively enter her work requires putting aside any attachments to high art, or even to particular art forms, and simply go with the flow of the exhibition.

Two Coats of Paint Fundraising Update: After nearly eight weeks, we’re inching toward our fundraising goal. Thank you, readers, for your generous csipport. If you enjoy our art coverage and have not yet contributed, please consider making a tax-deductible donation. Help keep Two Coats going in 2022. Thank you! Click here to contribute.

Taeuber-Arp was the youngest of five siblings. Her father was German, her mother Swiss. He died when she was two, after which her mother moved the family to Germany, ran a fabric shop, and taught her daughter to sew. As a teenager, Taeuber-Arp studied crafts and worked with master craftspeople, first in Switzerland and then in Munich and Hamburg. Her crafts education was rigorous and included studying textiles, mastering weaving, turning wood, and soldering metal. In 1915, Taeuber-Arp returned from her studies in Germany to Zrich, where she met Jean (also known as Hans) Arp, one of the founders of Dada; they would marry in 1922. In 1916, she and Arp hung out with the revolutionary Dadaists at the Caf Voltaire, where she performed as a dancer, made marionettes, designed sets for them and, most famously, rendered around eight elegant and wacky Dada heads, which closely resemble the egg-shaped props hatmakers use. All the while, from 1916 to 1929, she taught weaving and textile arts at a prestigious crafts school in Zrich.

During the 1920s, Taeuber-Arp and her husband each made art individually, and although this isnt stressed in the exhibition frequently collaborated on art projects. They traveled in Italy and Spain, often with other avant-garde artists, and became French citizens. While living in Strasbourg (a French city), Taeuber-Arp earned a commission to redesign and decorate the Aubette, an eighteenth-century public building, in the neoplastic style that celebrated pure geometric abstraction. Arp and Theo van Doesburg later joined her on the project, and, as with so many women in the story of modern art, Taeuber-Arp never received full credit for her equal participation in rendering this modern public space. (The building opened in 1928, but the public disliked it; much of the work was covered over and only recently was partially restored.) In Paris late in the decade, Taeuber-Arp designed a house for herself and her husband along with some of its furniture, which was modern and handsome but not particularly distinctive. In the 1930s, she turned increasingly towards more traditional art objects, such as oil paintings, wood reliefs, and sculpture. In 1937, she helped found the art magazine Plastique, which lasted for two years. The Nazi occupation of Paris in April 1940 forced the couple to retreat to the south of France, where Taeuber-Arp confined herself to making line drawings suggestive of Dada automatism. When the Nazis pushed south in 1942, she and Arp returned to Switzerland, where Taeuber-Arp died the following year from carbon monoxide poisoning caused by a faulty heater.

Although Taeuber-Arp was a practicing artist during the two horrific world wars, her spirit remained optimistic, and her version of modernism was joyous rather than anxious. Like other modern artists of her era most of whom were male she embraced modernism with her whole being. Unlike Kandinsky or Mondrian, however, she didnt have highly abstract spiritual ambitions. Instead, her aim was to move art down from its lofty perch and embed it in daily life. Modernist that she was, she sought to accomplish through the beauty of pure color and geometry. Although some of her work is abstracted figuration rather than pure abstraction, her focus is mostly on color, shape, and line.

An early Dada enthusiast, Taeuber-Arp aligned with the more playful antics side of the movement as opposed to its nihilist faction. Yet for all the fun she clearly had, she exuded a serious love of abstract art, and soon backed away from Dadaism. In a 1922 essay, she asked why conceive ornaments and color combinations when there are so many more practical and especially more necessary things to do? For her the answer lay in a deep and primeval urge to make the things we own more beautiful. Or, as she said elsewhere, the intrinsic decorative urge should not be eradicated. It is one of humankinds deep-rooted primordial urges. In other words, decorative and beautiful are not mutually exclusive for Taeuber-Arp. Making tablecloths, purses, necklaces, rugs or woven wall hangings is as worthy as making paintings or sculpture or practicing architecture. For todays abstract artists, fretting over the relevance of abstraction in our own complicated times, Taeuber-Arps work has a penetrating and resonant message: embrace the B-word, understand the principle that the beautiful is useful, and bring the beauty of abstraction into ordinary life.

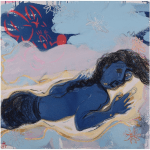

25 9/16 19 11/16 inches, Private collection

While the central significance of the exhibition is its collective cultural thrust, certain individual works do stand out. To my eye, the best, hands-down, are the artists grid-based, color-saturated weavings based on her gouaches and pencil drawings. Some are doll-sized wall hangings, others serve as small womens purses, still others are mid-sized wall pieces. Their exquisite and technically perfect stitchery, replete color, and geometric elegance stand to knock the socks off anyone not deadened to aesthetics. I am no weaver, but her textile work seems on a par with that of Annie Albers and creates a grid as powerful as Mondrians painted vertical and horizontal lines. As a painter, I couldnt help but linger over Taeuber-Arps paintings. By the 1930s, she was emancipating herself from the grid, with superior results. In Figures (1928), the shapes are interesting enough, but, stuck to an implied grid, they look stiff. In Equilibrium (1932), with the grid gone, the artists embrace of the constructivist diagonal structure lets the painting breathe.

Two of her most compelling paintings are Yellow Form (1935) and Planes Outlined in Curves (1935), each as bold, minimalist, and lively as an Ellsworth Kelly. The simple gouache on paper titled Head (1936) is a graphic precursor to her brilliant unpainted turned wood sculpture of the same title, which at first glance seems entirely abstract but in fact alludes to a gnome popular with German children at the time. Wood Relief (1937) all wood reliefs are first cousins to painting is an ebullient rondo with ivory-colored, slow-swirling shapes. Too many of the circle paintings and circle wood reliefs that Taeuber-Arp made in the thirties by then she had joined the abstract painting group Cercle/Carre just seem like big dots. The lovely exception is Animated Circle Picture (1934), with its precariously balanced blue circles floating on a white ground.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp was one of the boldest artists of her time maybe even matching Picasso, albeit in very different way and this brilliant exhibition is an important moment in museums ongoing effort to recognize under-acknowledged female artists. But her legacy extends well beyond being a courageously enterprising woman in a sea of men and an outstanding multidisciplinary artist. More fundamentally, she broadened the purpose of abstract art so that it fused with the decorative arts, making its beauty more accessible to all.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction, Museum of Modern Art, 11 W. 53rd Street, New York, NY. Through March 12, 2022. Before coming to MoMA, the exhibition appeared at the Kunstmuseum Basel and at the Tate Modern in London, where it was the first retrospective of the artist in the United Kingdom.

About the author: Laurie Fendrich is a painter, writer, and professor emerita of fine arts at Hofstra University.

Related posts:

A Two Coats Conversation with Stephen Westfall

The stories we choose to tell: Fall Reveal at MoMA

Finding Esphyr Slobdokina

Insightful review.

Excellent insights – most enjoyable review!