Contributed by Peter Malone / If I were inclined to embrace the humor in Meredith Rosen Gallerys anatomically titled group show, “Toes, Knees, Shoulders, Heads + Butts & Guts,” I would call it an impressive feat. But I prefer to call it both ambitious and largely successful in overcoming its own distracting arrangement. Bringing 23 substantial artists into a semi-raw space with a counterintuitive Upper East Side address needed no embellishment beyond its David and Goliath subtext. Combining the roles of curator and participating artist, Zak Kitnick, in collaboration with gallery director Meredith Rosen, swept an engaging mix of genres into a pair of compact exhibition rooms but unfortunately chose to match their choices to an installation plan emphasizing each pieces distance from the floor relevant to the human body. Though amusing and underlined by an assurance that each artist approved the idea, it added nothing to a visitors experience of the work, and in some instances trivialized it.

A few placements were no-brainers. Carl Andres Limestone Monocel (2009) sat on the floor. Anna Sophie-Bergers mud coat 1 (2016) was executed by proxy at the height of its proscribed gesture. Polly Apfelbaums Beads for April 15th Anniversary (2021) were pinned at ceiling height to focus the eye on its ceramic ballast, and Jorge Pardos Untitled (2013) ceiling lamps hung where one would expect to see them. The most literal was Hugh Haydens wall mounted Self Portrait of the Artist (2018) resembling a tree that protruded from the wall just above my head. And Kitnicks own Season 6000 (2020-21) metal backgammon board favored the space at the height of its own four legs. Other pieces were subjected to harmless tweaks, like Harry Moritzs, The Red Light Inside Me (2020), a refrigerator door installed at gut level, where refrigerators tend to reside in ones pre-lunch imagination.

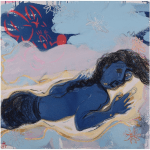

I was more impressed with how the selection punched through the mythic wall of canonic status, placing Andre outside Minimalisms mystification of volumetric space. There was more substance to the shows mild revisionism than to its embrace of a distracting body-level theme, which led to awkward installation decisions. An example was the the needlessly risky placement of a glazed ceramic piece by Hadi Fallahpisheh titled, Persian Cat Sam (Mouse House) (2020) inches from my foot. Its vulnerability superseded the whimsy of its theme conformity, especially in a small room. Worse still was the hanging of Peter Eisenmans axonometric drawing at ceiling height which changed its purely functional distortion into an expression of drooping elasticity. Witty I admit, considering Eisenmans penchant for visual absurdity, but impertinent to the project represented in the drawing. Anybodys axonometric drawing would have delivered the same punchline. Equally problematic was the placement of a floral watercolor submitted by Amy Sillman, Untitled (no date) that was installed at garden level, or knee level according to the operative metaphor, that made engaging with it as a painting all but impossible.

The idea of body levels informing placement would have been a forgivable conceit had it not trivialized some of the work. Fortunately, there was enough space left at conventional eye level to install other pieces that begged for close examination, especially Jacob KassaysUntitled, (2013), a miniature library inside a book, Huma Bhahbas Untitled (2007) hybrid of ink drawing and digital photography, and Viennese expat Rudolf Schindlers masterful mid-century rendering Medical Building (1945). Putting the quality of the art aside for a moment a suggestion that I hope sounds as strange to the reader as it does to the critic writing it this arrangement was as notable for its adroit realizations as it was for its obdurate miscues, neither of which made the work more compelling than when it left the artists studio.

From its inception, the plan compromised the essential curatorial function of caretaker, an understandable but crucial misstep. As a former gallery director, Im sympathetic with others facing the pressures of unifying a broadly selected group show by emphasizing a common property that might otherwise go unnoticed. But this exhibition was fragmented, not unified, by its premise. Maia Ruth Lees painting Bondage Baggage Atlas (2021) looked as if it were installed in the only space left, there being no perceptible reason for its placement near the floor other than conformity to an artificial scheme.

As modest venues bob and sway in the wake of hyperbolic dreadnaughts like Zwirner, Gagosian and Pace, the importance of our small independent galleries increases. And as the growing ranks of independent curators amplify the competition at the gatekeeper level, artists risk losing more control over their works context. Wed do well to remember that modernisms fundamental achievement was the liberation of artists from meddling patronage including the well-intentioned sort.

Toes, Knees, Shoulders, Heads + Butts & Guts, featuring Carl Andre, Polly Apfelbaum, Lynda Benglis, Huma Bhabha, Anna-Sophie Berger, Tom Burr, Peter Eisenman, Hadi Fallahpisheh, Francesco Galetto, Rachel Harrison, Hugh Hayden, Madeline Hollander, Jacob Kassay, Zak Kitnick, Maia Ruth Lee, Anne Libby, Harry Moritz, Jorge Pardo, Luther Price, Rudolf Schindler, Amy Sillman, Paul Virilio, Anicka Yi. Curated by Zak Kitnick and Meredith Rosen, Meredith Rosen Gallery, UES, 11 East 80th Street, New York, NY. Through July 17, 2021.

About the author: Peter Malone is a painter who writes about art. He is currently represented by the Silas von Morisse Gallery in New York

Related posts:

Amy Sillman: The O-G Volume 3

Jacob Kassay: Familiarity superseding reflection?

�modernism�s failed achievement is the liberation of artists from meddling�gatekeepers��of all sorts. Then it�s not only the failure of an epoch, but the failure of all religio-political pyramid-scheme societies.

https://archive.org/details/osho_e119/05+Meditation%2C+the+method+of+great+liberation.mp3

�Minimalism�s mystification of volumetric space� When Baroque and the ornamentalism of the Belle �poque became gaudy, Bauhaus movement in architecture, industrial and fashion design�the Minimalistic zeitgeist came to the fore, but that is merely a reactionary, repressive taste of a modernist saint, a self-flagellation of taste. ?