Contributed by Rebecca Chace / Julie Heffernan is primarily known for her large-scale figurative paintings that seamlessly merge a rococo sensibility with contemporary content. Since “Hunter Gatherer,” her 2018 solo show at PPOW in New York, she has been working on her first graphic novel, fusing drawing with memoir and narrative. We recently sat down in her Brooklyn backyard to talk about this new direction in her work.

Rebecca Chace: So, why did you decide after all these decades of painting to write a graphic novel?

Julie Heffernan: Well, I had just had a big New York show, and it was so detailed, and so much about a lifetime of looking really hard and intensely at imagery, that I felt like I needed to shift that focus to something that could tell a story more directly. I’ve also been doing slide lectures for umpteen years and developed a particularstory, since I’m not the kind of person who really likes slide shows where artists say and then I did this, and then I did that. So, over time in my lectures I�ve developed a story that has to do with growing up Catholic with no art in the house, and kind of finding yourself through painting, and discovering that paintings can hold wisdom and secrets.

RC: Do you mean the act of painting, studying painting, or both?

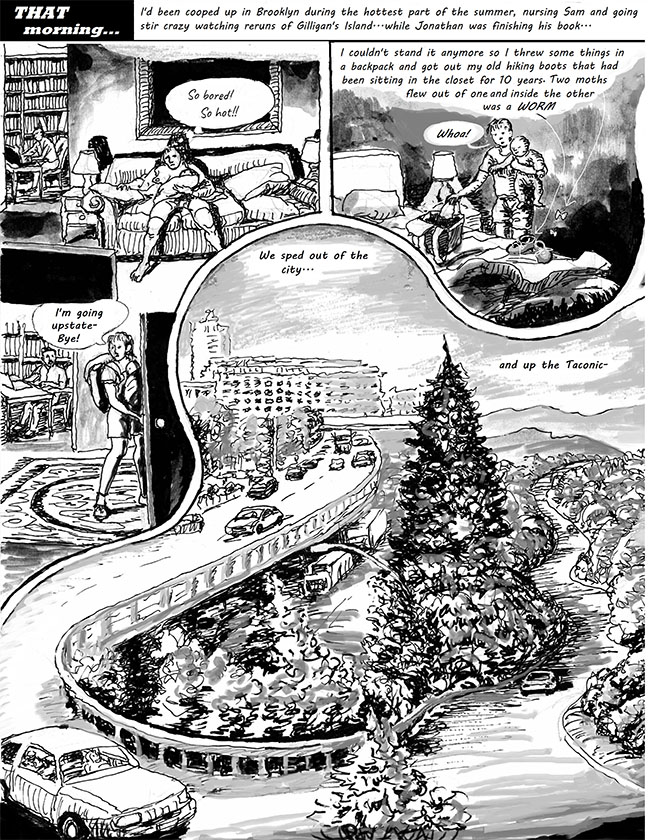

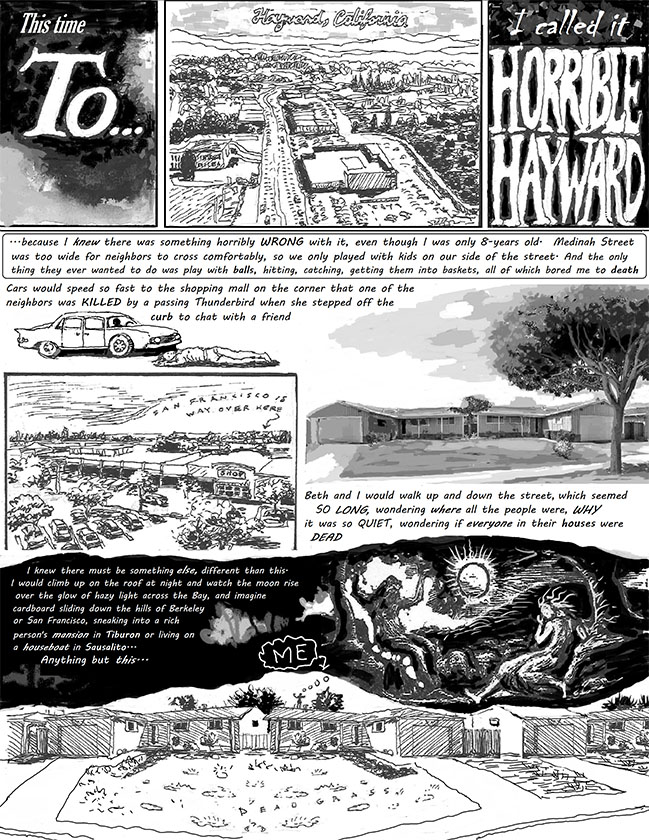

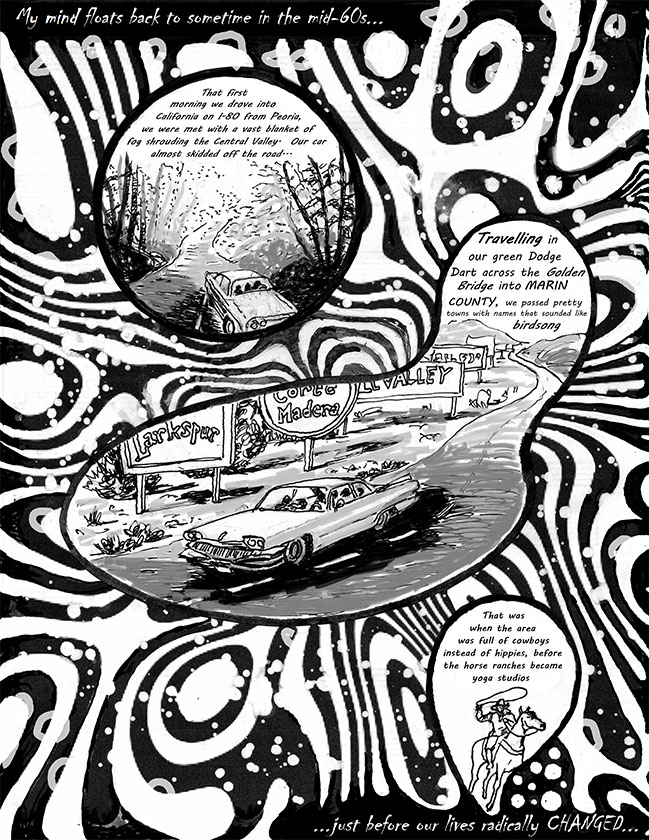

JH: Both. I would talk to art historians and tell them what I saw in a painting and they’d say, wow, I never looked at it that way. So, it gave me a sense that as a painter, I was onto something, and the graphic novel gave me a way to express that. My graphic novel is loosely, the story of how I came to be an artist, the story of my work and also about the way I look at paintings. So, it’s like three stories folded in one. When the novel starts out, I’m lost in the woods with a baby, and as I’m wandering, I’m remembering being a kid and moving with my family to California from Peoria, Illinois. Midwesterners to the promised land, you know, and then the squabbling in our family and how debilitating it was, and then my mind shifts to Giotto’s Massacre of the Innocents, and how it’s a meditation on power struggles. It parses the subtleties of power relationships, both literally and formally in its visual construction, and you can really only analyze it in depth by using visuals, like in slide talks. You wouldn’t write about it in a book, we wouldn’t want to read it. You want to see it. There’s paintings that give you wisdom and tell you secrets, and there’s paintings that lie to you, glorifying things like rape, like in so many paintings of Greek myths that we�re reared on, or that I was reared up on. And then you become an adult and you go, wait a minute, there�s rape everywhere. Rape and vainglory.

RC: Yes, that was clearly one of the currents running through your most recent show, which was very consciously feminist, in response to the #MeToo movement, with Old Master style images of women you were honoring. There was also a reference to Carol Schneemann in that show, with a self-portrait holding a scroll, and now that we’re talking about it, I mean, those scrolls were almost like graphic novels.

JH: Yeah, you’re absolutely right, and who knew? I mean, Carol Schneemann, yes, but what I didn’t do was make any linkages between the images in that scroll and this graphic novel now.

RC: That reminds me of something that you said in one of your early artist statements, that your paintings were coming from an image stream inside your head, kind of like watching a movie. I can see the connection to the sequence of frames in a graphic novel, but I wonder if this image stream also has a connection to some of those secrets you find in paintings?

JH: Right, well, it’s certainly a way that I see things. But I do research too, and depend on intuitive links to bring things together, although intuition is useless without expertise, I gotta say.

RC: Your paintings are so rich with images and objects, there’s a lot of different entry points for the viewer. With graphic novels, you have images, but we’re also being led down a specific path by the words.

JH: I love the way the eye travels through a painting. You travel along certain planes, but you also travel in space, you know? You can go way back to that distant deep space and see what’s going on, and then jump back to the foreground and see what’s going on there. Even better, what happens when the meaning of something in the foreground changes when juxtaposed with something behind it�conflation of space.

RC: You do that a lot, I mean, in many of your paintings there’s this whole other world further away, and if I could use a spyglass, I could see that other world.

JH: I remember when I was first showing a hundred years ago, David Bowie came into the gallery and said to the dealer, she should be doing CD-ROMs, and I didn’t even know what that meant. I still don’t think I know what it means! But the idea is that there should be wormholes in the paintings that can take you deeper. I always loved that idea. This graphic novel is a version of doing that. I can telescope way, way back to Peoria, you know, and then be hitting a rock with my foot in the foreground. I mean, any writer does that, but it’s how I can think about it and express it visually.

RC: Do you feel like painting has failed you at this point in your life? Or do you feel like a new door has opened and you actually find yourself a little surprised that you don’t miss painting? Or do you miss painting?

JH: I mean, I love painting! I would literally run to the studio every day, for 30 years! I just think, you know, I got a divorce, or maybe a temporary separation, and now I’m having an affair.

RC (laughing): Yeah, I get it, like a different aspect of yourself being revealed. Though, it actually seems very connected, your impulse toward seeing things in frames and narrative painting leading to the graphic novel. Also, using yourself as protagonist is a continuation of the use of self-portraits in your painting. In your recent work these self-portraits are very self-sufficient with these wonderful tool belts equipped with books, and paintbrushes and canteens. Is it going to be similar in the graphic novel.

JH: Not really, because in the novel, I am completely useless. I’m a bad mother. When Sam [Heffernan’s younger son] was a little baby, I took off for the Berkshires. I really just wanted to hike a mountain and then come down and go home, but instead got really lost and ended up on the other side of the mountain, with a baby! wearing street shoes! It was one of the stupidest things you could ever do. It worked out because eventually I just headed straight down the mountain, and the Berkshires aren’t huge. But if it had been the Sierra Nevadas, I’d be dead. In the novel, she actually has to spend the night. And then, you know, what am I going to eat? How am I going to drink?

RC: So, in some ways you are referencing those images in your paintings of women surviving in a sort of mythical wilderness, making shelters, and with the baby you’re incorporating motherhood as well, as you have done in your paintings. That’s really interesting.

JH: And some of my paintings are reproduced in the novel as well.

RC: Let’s talk about technique for a minute. You’re using a drawing program for the novel, right? Working on a computer instead of paper.

JH: It’s called Microsoft Paint, and it’s a real dinosaur of a program. I mean, I didn’t do any research. I didn’t want to get caught in the technology weeds. The guy at Best Buy said, if you get this computer you can draw on it with the pen. So I got it.

RC: This is literally a laptop, it’s not even a “pad” of some kind. But that is physically such a different thing to be doing than painting. I mean, on the most basic level, you’re not standing and painting. As a writer, I’ve always been so jealous of painters getting to move around and listen to music as they work, when I’m just sitting silently at my desk.

JH: Yeah, that�s the biggest deficit to the experience, because normally I would be jumping up and down all day, painting. Yeah, I miss that a little bit. So, so different. And on a practical level, it was also�Wait! I don’t know what I’m doing! and for a while I was postponing the inevitable. I bought the computer and didn’t even open it for five months because it was so intimidating. But then, I really took to it.

RC: And it doesn’t feel any less creative to you, sitting at the desk, working with a program on the computer?

JH: No.

RC: Wow. What’s the relationship between how you’re creating the image and what language you’re using? Did you start with the drawing, or did you go to language first?

JH: I wrote the manuscript first, I mean a lot of pages. Then I started basically from the beginning, drawing. Here she is on the mountain and I’d draw one frame, then another and another and then pull in text. I�d look at it a week later and redesign the whole page, add six more, take out three. Still doing that.

RC: So you’d pull things directly from the written draft, but then sometimes, I assume you’d just throw it away and write something new.

JH: Yeah, that’s when I discovered that a lot of things that I plunked in from the manuscript draft ended up not working at all.

RC: That’s interesting.

JH: Yeah, just stupid, wordy, embarrassing�a horrible thing.

RC (laughing): Just like any writer with their first draft.

JH: And now I’ve finished an entire draft with words and images and I’m super excited to toss out as much as needed.

RC: It sounds like this is a gathering together of all these different aspects of your life. Your painter self, your teacher self, your childhood into adulthood self, and your storytelling self.

JH: Yes. What have we learned by getting older? Maybe we’ve earned the right to say: all this stuff happened, and maybe it’s worth looking at again. I feel so lucky, I feel like everybody should do this, find a way to bring their different selves into another kind of expression.

RC: And so many artists do that somehow, at different points in their lives.

JH: Yes, and for me, this is absolutely the next step�maybe not forever; I mean, I have been a narrative painter all my life�but I found I kept drifting away from the painting wall back over to the laptop. Weird, but Ok. Time to stop. And keep moving.

About the artist: Julie Heffernan is a Professor of Fine Arts at Montclair State University, represented by Catharine Clark Gallery in San Francisco. Heffernan is the recipient of numerous grants including an NEA, NYFA and Fullbright Fellowship. Her work has been reviewed by major publications including the New York Times, Art in America and Artforum; and in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum and VMFA among others.

About the Author: Rebecca Chace is the author of Leaving Rock Harbor; Capture the Flag; Chautauqua Summer; June Sparrow and The Million Dollar Penny. She has written for the New York Times Magazine, New York Times Sunday Book Review, the Huffington Post, The LA Review of Books, Guernica Magazine, Lit Hub, NPR�s All Things Considered and other publications.

She is associate professor in Creative Writing and Director of the MA Program in Literature and Creative Writing at Fairleigh Dickinson University.

________________

NOTE: Today kicks off the third week of the Two Coats of Paint year-end fundraising campaign. Please consider a tax-deductible contribution to keep Two Coats going in 2021. Thank you! Click here.

_________________

Related Posts:

Michelle Vaughan presents forty conservative women

Tracking proto-feminist Loren MacIver

Farley Aguilar�s screamingly urgent figurative paintings