Contributed by Sangram Majumdar / Recently, I have been admiring the images of Meghan Brady’s large-scale works on paper that she’s been posting on Instagram. The images prompted me to revisit the narrative I had arrived at about her work, and to investigate further. So, on the occasion of her current exhibition “Said + Done” at Mrs., I reached out to the artist to learn more about this new body of work.

Sangram Majumdar: How did this series come about?

Meghan Brady: I started this body of work (all stretched canvas) by laying them on the floor and using only acrylic paint for the initial moves, just as a way to start them the same way that I start the large paper collages. Nothing revolutionary but more an attempt to align two modes of working. The acrylic is fast and unfussy and bright, and so the pace and timing of how the first stage of the painting evolves lines up with my jumping off excitement of starting. That said, these paintings feel part of everything I’ve made before and just building blocks of the world I am slowly, irrationally trying to carve out in my studio.

SM: The title of your show at Mrs. is “Said + Done.” I know in the press release it talks about the dual/opposing modes of communication, but was wondering if you’d expand on it a bit more.

MB: The title is meant to parallel and oppose verbal / written communication and the act of doing / making. And it’s not lost on me that titling a show with a colloquialism for a quick and tidy completion – that it’s a ridiculous title for a show that was meant to happen in April and then was postponed because of the pandemic.

And being physically distanced from everyone during this pandemic has me thinking of painting as a signal, a communication… though not a clear one. It has many moods, like us.

The deeper I get into this project, the more I appreciate the layered knowledge and freedom of doing something over and over. And especially the knowledge that seems to be held in the body when making something. I mean, obviously, it’s in the brain but I am playfully wrestling with the opposing forces of the mind and body in the studio realm. You know how you can almost feel what decision to make in a painting in your arms and hands before your mind has the clear thought? There’s something about the studio, being an artist, that forces one to prioritize the less-linear, the less explainable because making a life as an artist makes very little sense to begin with.

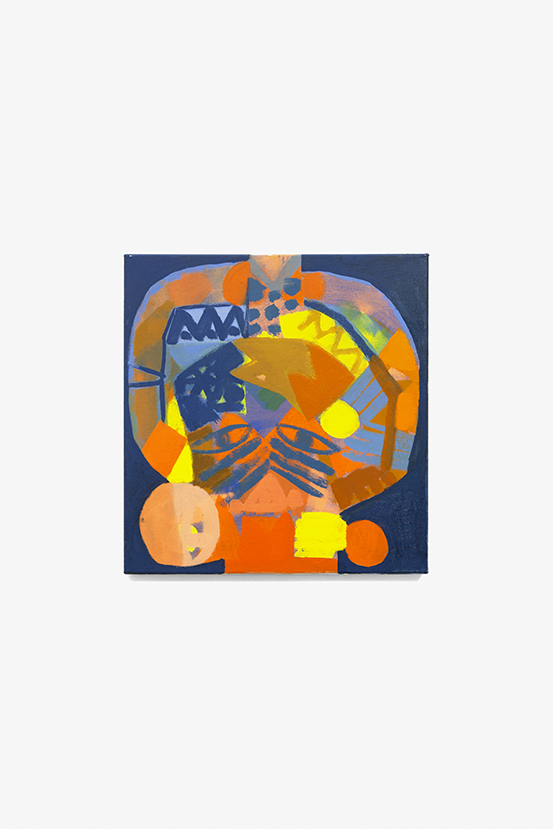

SM: The body/mind, doing/making ideas make me think of how in many of your paintings, such as Lionblaze, there is a central form that clearly reads as eyes. It’s almost like a location. Meanwhile, other forms feel like pathways guiding our journey through the painting. Is this an example of the “opposing forces” of the body/mind or doing/naming?

I don’t think that I distinguish this clearly between the two while actually painting but it’s a fitting observation. The more representational elements do act more as pins to slow some of the other movement down – I can see that looking at this now. I make the parts of the painting that are more linear as a way to contain or balance the movement of the bigger underlying moves. The “signs” as you call them usually filter down from the linear moves.

SM: Staying on the motif of the body, I have read elsewhere you using the phrases “body intelligence” and “turning my back … on painting.” Why did you feel you had to “turn your back” on painting to move forward?

MB: Hearing / reading the phrase of turning my back on painting sounds so cold and harsh but I meant that more as a move away in order to find my way back. Starting the big paper paintings was a liberating process for me (no cumbersome stretchers, cheap materials, the chance to completely rearrange at any given point). I look at the paintings that I made for a show right before starting the paper-work and the paintings look so claustrophobic. It’s oversimplifying to chalk it up to a larger space and a translation between materials and a shifting of scale because there were other forces at play. I had begun to feel as if I was overworking my surfaces and the visual effect was bogged down and exhausting. I love painting and I wanted to show that in a direct way and not get caught up in some played out narrative about the importance of painting.

SM: Looking at this group of paintings, I am struck by how much light they emit. In Sonny and Everyday 2 high key mixtures sit right against hues at full chromatic blast. The drawing as well feels “light” and almost aloof in how they skirt legibility, teasing and suggesting readings. And often the ground color peeks through and/or frames a central structure allowing us to move in and out, bringing with it a sense of light and air. What do you think about this reading?

MB: Yes, totally, that’s a good read. The paintings really are built from the first layer up and I often try to loop the painting back together by keeping the freshest layer in conversation with the oldest, furthest down color. While this doesn’t relate to my painting directly, I am an admirer of Louise Fishman’s paintings and the sense that she is sometimes mining layers and bringing a fire or gem of paint back to the surface by digging through. I love how this makes the painting have its own time and history and sense of light.

SM: Something that I have always admired and noticed in your work is how you structure/build your images. There seems to be an innate sense of structure present on multiple levels – in their actual making as well as how the “make” and “unmake” visually. Also it seems to be a running thread thematically. In earlier work the forms seem almost architectural, angular, sharp, while the newer work is directly engaging with shapes and marks that evoke the body. What do you think about this?

MB: I love that reading. I want my paintings to be approachable and friendly but mysterious things, things you want to look at but not necessarily understand right away. And a painting that shows how it was made is an ingredient that feels right to me – a way to draw the viewer in and show the painting’s imperfection.

SM: Is this where “looking” in a way becomes a bridge between the body and mind as well?

MB: Looking is a kind of thinking, of course, and I actively push against the pressure to be productive in my studio all of the time. Sure, I have deadlines, I need to take care of things, and time is a privilege but the studio can feel like such a rebellious respite from our culture of busy-ness. Looking is anti-busy.

SM: Currently you and your partner, Gideon Bok, both have shows up. I have never made this connection before, but thinking about both your works, I realized that there is a sense of immateriality, gesture, and a constant state of flux in both of your works. In your work especially, the paintings and works on paper seem to build almost from within, but/and especially in the collages, the fact that we can “see” the individual strips of paper attached allows me to imagine them before they were affixed but also the promise of them moving again. It reminds me of seeing the numerous pin holes at the edges of all the cut paper shapes of Matisse’s paper works in “The Cut-Outs” exhibition at MoMA. It seems both of you are at home with change.

MB: I think that change thing you are seeing is a fundamental aspect of our paintings and our studio lives and maybe even our whole life philosophy – that it is all in the search and in the search you must be willing to lose what you thought was working. But I think there is a kind of searching, in Gideon’s work especially, that is humbly and hopefully trying to solve a visual riddle that is ultimately impossible to solve.

SM: Do you think what painting means to you has changed in the recent years, and especially now with everything going on in the world?

MB: Yes, I think what painting means to me has changed especially considering everything that is unfolding at this moment. In the broadest sense, a painting made now is a painting about now, right? And I feel that painting, like us humans, is more expansive, more flawed, more restless, more open. It’s really exciting and I feel so lucky to be a very small part of the mix.

“Meghan Brady: Said + Done,” Mrs. Gallery, 60-40 56th Drive, Maspeth, NY. Through November 7, 2020.

About the author: Born in Kolkata, India,Sangram Majumdar is a Professor of Painting at the Maryland Institute College of Art.

Related posts:

The Abstract Zeitgeist in Storrs

What good is abstract painting now?

Schwabsky coins the term “retromodernism” for work that references postwar-era abstract easel painting

In the attic: Abstract easel paintings from 1920-50