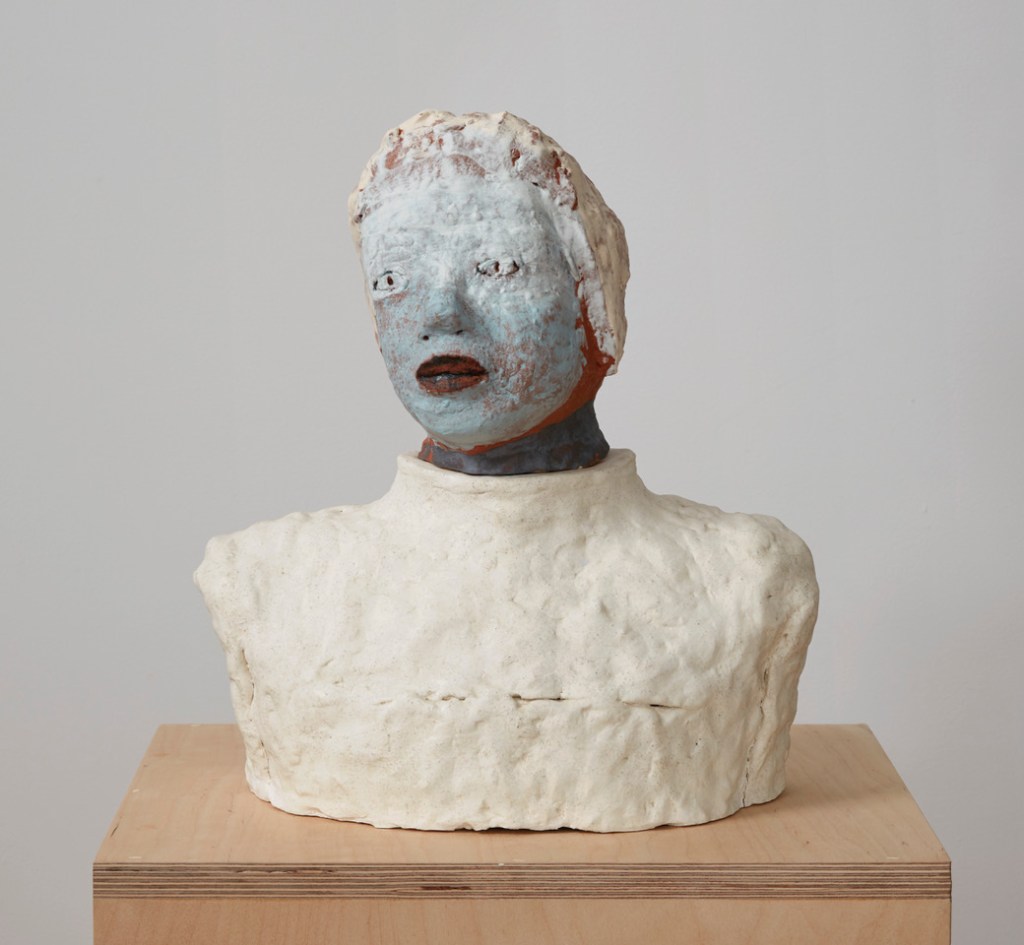

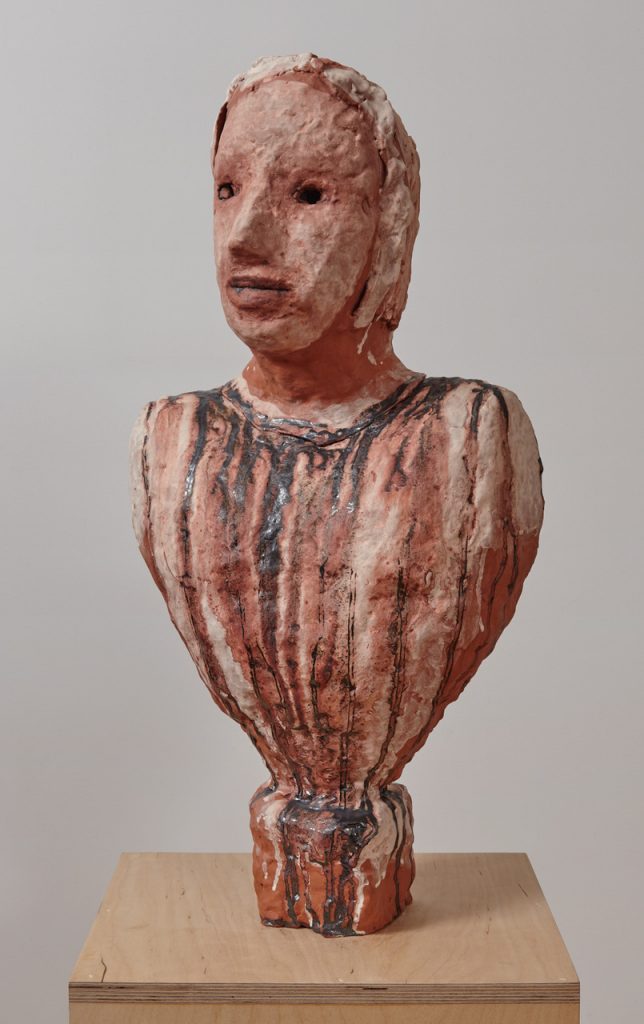

Contributed by Leslie Wayne / For as long as I�ve known Elise Siegel, she has been making three-dimensional work about the psyche. Although her sculptures have always addressed the body in some form or another, her subject has always been the mind. In the 90s, she made skirts and dresses from wire mesh and acrylic modelling paste, accentuating the patched together, bandaged and cracked surfaces of the material, questioning the value we place on fashion to provide both identity and protection. In 1999, she returned to clay, a material she had studied extensively in school and created 30 heads which she placed on the floor like ghostly dismembered personages rising from the depths. She went on from there and made body parts out of clay, such as tightly clasped hands, and arms dangling from ropes on a wall. The body continued to remain fragmented, and throughout the early to mid 2000s she focused on ambitious installations of life-size clay figures. Her 2001 installation, �Into the room of dream/dread, I abrupt awake clapping� consisted of eight children seated on wooden chairs in a loose circle, all looking in the same direction with their hands silently clapping. Their little outturned and nearly identical faces were quizzical as if to ask the viewer to interpret the game in which they were engaged. In 2004 her installations, �Twenty-one Torsos, Twenty-four Feet� comprised of children�s hollowed out bodies divided into upper and lower halves, the uppers perched on rolling stands with arms waving about in apparent mayhem, and the lower bodies seated on two rows of chairs facing each other so that their stockinged and flexed feet gingerly touched each other. It was a powerful evocation of psychological innocence and aggression. Since then she has returned to the head, more accurately the portrait bust. For these, Siegel draws inspiration from a broad range of cultures and periods, from the Jomon Dogu figures of Neolithic Japan to Renaissance reliquary busts and African masks. I had the pleasure of visiting her studio as she was preparing for her upcoming solo show at Studio 10 in Bushwick, which is on view through February 3.

Leslie Wayne: Elise, I love coming into your studio. It feels so fully inhabited by these characters. Although I think I should qualify my use of the word character because each bust, while it has a fairly distinct expression, color, and posture, there is a kind of anonymity to them as a collective. I mean they don�t really look like portraits of anyone in particular but rather seem to represent the idea of �character.� Is that accurate?

Elise Siegel: I think you�ve hit on a couple of things. The anonymous crowd and the idea of �character� make a lot of sense to me. Any crowd of people seems anonymous unless you already know the individuals, such as a crowd of people waiting on a subway platform. But once you fix your attention on one person, you start to create a mental narrative around them, based on their facial expression, body language, their clothing etc. among other things. You still don�t know them, but you respond to various cues that are available to you. The things you pick up on and the story you construct say as much about you as they do about the person you�re observing.

On a certain level, the experience you�re describing in my studio might not be all that different. When you first walk in you confront a crowd. Once you begin to engage with individual sculptures, you start to construct narratives. But even though you might be drawn in, you�re also aware they are not real living people, and the narratives retain a fictional quality. So the sculptures can be seen (or felt) as �characters� in the stories you tell yourself about them.

In this work, I am definitely not trying to depict an individual, or even a very specific emotion, or experience. What I really want is to allow the sculptures to be suggestive, but indeterminate; to draw a viewer in and be responsive to whatever that viewer brings to the encounter.

I think we have the capacity to connect with and respond to sculpture in an immediate, physical and emotional way partly because we inhabit the same space. We are in the same world and not separate from it.

LW: That�s true, and figurative sculpture in particular demands a very different response from the viewer than painting does because of its corporeality. Though to your earlier point about their being suggestive but indeterminate, I will say that I find the expressions you give them to be decidedly, if not distressed, then somewhat dazed. They�re not exactly neutral. Something�s going on inside of them that projects a very strong feeling, even though they are not representing anyone or anything in particular.

ES: I love that word � dazed. I have often used it to describe how I feel after wrestling with a piece in my studio, so it makes perfect sense that some of the busts reflect that. They almost never become who they are without a struggle and often they�re on the brink of destruction before I finally let them be. Many of them have been through quite an ordeal.

When I begin working on a sculpture I�ll have some formal ideas I�m interested in exploring, but in terms of what an individual piece is going to say or express � that is something I only discover through the process of making it. I might get some early sightings, but I don�t fully recognize it until it�s looking back at me and basically, staring me in the face. By this point the sculpture has been through many iterations, and I�ve been through a few changes myself. In other words, we�ve had a long conversation. Hopefully, the finished sculpture retains traces of the entire experience.

LW: I think they do! And the idea of portraiture as a reflection of the artist is of course a very Modernist idea. I notice they are also almost always female. Are these all really just self-portraits that compel themselves upon you, in spite of your best intentions to � and to be fair, successes at – incorporating other cultures, modes and ideas? I mean, at the end of the day, I think that sometimes we just can�t help ourselves.

ES: I can see where you�re coming from. As a sculptural idiom portrait busts have a very long history and come with a set of expectations. A portrait bust raises the obvious question: who is it? If it is not an honored personage, or someone known to the artist, or even a person they�ve thought about, who could it be but the artist herself?

Most of the busts do seem more female than male and they are definitely a reflection of certain aspects of my own psyche.

Even some of the elements from other cultures that I�ve incorporated are things I�ve had a strong attachment to ever since I started making art, and in some cases even since childhood. I have visceral memories of early visits to the African and medieval armor galleries at the Met, entranced as well as scared stiff by the power of some of their imagery. My introduction to the Jomon period came from my favorite teacher in art school, and I admit to having created a series of Haniwah inflected totems soon after graduating! I guess I would say these things are part of me too.

So the busts incorporate various aspects of my lived experience, as a female person, as a child, as an artist, etc. They have a lot of me in them. But I would not call them self-portraits. It points in the wrong direction. I want them to be as much about the viewer as they are about me.

I think of them as sculptural objects that take the very familiar form of portrait busts, but then subvert some of the expectations that are triggered by that initial sense of familiarity. Hopefully, there can be a moment of encounter, when things shift and feel a little less certain, or out of balance, allowing something more unexpected to occur.

LW: Fair enough. I recall a similar discussion I had with Philip Glass once who was speaking at MoMA about Chuck Close�s work. I asked him if the intense scrutiny of Close�s faces were an investigation of his own mortality and he adamantly replied no! My father was a shrink so my natural inclination is to always go to the psychological. But I appreciate that that is not everyone�s primary focus!

So let me ask you about something else. I have always sensed that you have a very profound relationship to the material and a real hands-on love of the craft. Happily, clay is having a long overdue moment of recognition as a valid material with which to make meaningful art. How ridiculous. Well anyway, thank goodness for that and how great for you. Today we�re seeing work of everyone from Viola Frey, Andrew Lord, and Betty Woodman to mid-career artists like Kathy Butterly, Rebecca Warren, and Jessica Jackson Hutchins to younger artists like Matt Wedel, Jessica Stoller, Francesca DiMattio, and Brie Ruais. That�s quite a community. Do you see yourself as a fellow ceramic artist or as a sculptor who happens to be working in clay?

ES: Yes, I wholeheartedly agree. It�s great that clay is no longer sidelined in the art world. We’re lucky to be working at a time when there is more inclusivity and many of the old distinctions are losing their meanings.

To answer your question: I’m a sculptor working in clay. Though I majored in ceramics in art school, a few years after graduating I started to explore other materials.By the time I moved to New York in 1982, I was no longer working in clay. Over the next fifteen years I made and exhibited several significant bodies of workin other materials. It wasn�t until after my daughter was born in the mid 1990s that I returned to clay. I think my interest was rekindled for two reasons. First, I wanted to take the plunge into truly figurative work and clay seemed ideal for this. And I was also feeling the need for a material that could compete with the pleasures and demands of a newborn baby�something as seductive and sensuous as she was.

LW: I love that. Art rivaling life.

ES: Yes! They were and are still very intertwined. For me the meaning of what I do is very much embedded in process, in all the ways I connect to my material. I think of what I do as a kind of intimate interaction with the clay. It�s an engagement in the unpredictable present moment, rather than an attempt at control. As much as possible, I want everything I perceive and feel and do in this process to be revealed in the resulting object.

Clay feels alive. It has an incredible immediacy–an ability to respond to the smallest gesture, to accidents and events both within and beyond my conscious intent. It also has the capacity to register and record touch, to capture the experience of making.I also love that it�s been a primary material for creative human expression since pre-historic times.

LW: I know it�s a bit of a clich� to blame mechanization and the digital age for the increasing loss of craftsmanship, but there�s some truth to that argument. I would say that the preponderance of theoretical studies in schools is also responsible for sidelining making and the basic understanding of materials and craft. But some aspect of these trends are cyclical and I know from my husband Don [Porcaro] who taught for many years at Parsons that a new generation of students who grew up with computers and cell phones are craving – and demanding the experience of making things with their own hands. So I think there�s a great future ahead for what you are pursuing.

I agree and I think there are multiple factors leading people back to craft, including feminism and multiculturalism. But in this digital age, people are just feeling the need for hands on experience. I�ve been teaching atGreenwich House Pottery for many years and when I first began it was a slightly sleepy �well kept secret� in the Village. Today it�s bursting at the seams,more classes and artist residencies. I think it bodes well for all of us!

About the author: New York artist Leslie Wayne is represented by Jack Shainman Gallery in Chelsea. Wayne is an occasional writer and curator, and has received numerous grants and awards for her painting objects, including a 2017 John Simon Guggenhheim Foundation Fellowship.

Related posts:

Adirondack idyll: Jay Invitational of Clay, Rockwell Kent, Ausable Chasm & more

Ginny Casey: Disembodied hands and lumps of clay in Philadelphia

Objecthood: Joan Mir�s painted sculptures

“an engagement in the unpredictable present moment” – a great phrase, not just for how the artist describes her process, but how I experience her work; it is a thrilling engagement and then lasts more than a moment, of course.

What a great interview. Perceptive questions, and thoughtful, beautifully expressed answers. Really gave me a window into both Elise’s process and work. Want now to get in to see the work in person.

Thank you so much for this comment, Emily! This is exactly what I am thinking about and hoping will happen.

Such beautiful work, Elise. and Congratulations on your thoughtful conversation, Elise and Leslie, and it�s publication here! And thank you Sharon for Two Coats.

Wonderful work and informative article. I look forward to seeing the

show. Have you ever seen any examples of Toraja Tau Tau funerary sculpture from Indonesia? They might interest you.

Really engaging and amazing work. The interview is great.Thank you!

THanks, Marilyn! I will search for images.

Great interview! Your “sculptural objects” really do present themselves as intimately familiar on first approach, and then offer a bridge to a more ritualistic, transcendent sense of otherness. Wow, I look forward to seeing the show, Elise!

Great introduction to an artist worth knowing more about. I look forward to seeing the show. Beautiful work!