Ever since I’ve known artist-writer-curator Stephen Truax he has been in a state of what curator Anne Luther calls “hopeful doubt,” perpetually examining what painting and art might be in the 21st century. On the occasion of “How Will I Know,” his first NYC solo show, Two Coats of Paint invited Truax to share some of the ideas and influences that inform his work. Opening October 7 at 67 on Ludlow Street, the exhibition will include drawings, photographs, text, and sound pieces that explore a domestic involvement between a married couple and a third partner. “In these works,” curator Luther writes, “we find ourselves in the cruising ground, in the bedroom, in the car, and thus implicated in the activities that go on there. ‘How Will I Know’ proposes that personal life can be employed as a statement of continuing political urgency.”

–Sharon Butler, editor

1. Martin Kippenberger

Kippenberger, Susanne. Kippenberger: The Artist and His Families. Translated by Damion Searls. J & L Books, Atlanta and New York, 2012.

To lead life as a work of art. Kippenberger not only had meetings at the bar, he turned going to the bar into his work. His art production was dynamic–moving fluidly from medium to medium, letting each project dictate its own needs. He was unbelievably prolific despite his substance abuse problems and innumerable commitments. He was an artist (within this, he used painting, drawing, photography, sculpture, text, etc.), an art dealer, a curator, a writer, he ran a nightclub, the list goes on. I’m an artist and a writer, I organize exhibitions, and I work fulltime in a Chelsea gallery. Kippenberger makes me less afraid to be wearing so many hats.

2. Martin Boyce

To create a series of works around an abstract idea that grow and expand into different media and presentation methods. Boyce extrapolated from a simple Modernist design an entire body of work, including his own typeface, a tessellation pattern, and these expanded to sculptural and architectural elements, and an installation, for which he won the Turner Prize in 2011. Charlotte Higgins wrote in a profile at The Guardian:

Boyce talks about going to live in Berlin for a year in 2005 and deliberately taking nothing from his studio, moving into a large space with Simon Starling (yet another Turner prize winner from the Glasgow School of Art, this time in 2005). “We had this big long desk. He sat at one end, I sat at the other … after a couple of weeks of twiddling my thumbs, I needed something to start playing with.”So he got a friend to send him a book in which the Martels’ design was illustrated. He made models of the trees; but he found that when he laid the drawings out, he could also create a repeat pattern — and even find letters of the alphabet, a typeface as it were, within the shapes. The trees blossomed, he says, becoming for him a lexicon of shapes and forms. “I never imagined that, six years later, the tree would still be generating work.

I moved to Berlin in April 2014. I made a pact with myself not to make a completed work of art for one year. I stayed there until Christmas. This unstructured time to think and make in Berlin was helpful in reorienting my thinking about my work.

Martin Boyce has an upcoming solo exhibition at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, in May, 2017.

3. David Wojnarowicz

Wojnarowicz, David. Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, Vintage, New York, 1991.

Sometimes it’s like long ago and the words were slow and we were meeting beneath faraway rivers. (page 77)

Each painting, film, sculpture or page of writing I make represents to me a moment in the history of my body on this planet, in America. Therefore each [work] I make has built into it a particular frame of mind that only I can be sure of knowing, given that I have always felt alienated in this country, and thus have lived with this sensation of being an observer of my own life as it occurs. (page 149)

To fearlessly confront his audience with the radical nature of queer lifestyle, in particular his use of his own personal relationship with HIV/AIDS as a political tool. This specific historical period of late 1980s and early 1990s Romantic Conceptualism has become a touchstone for my current projects. Specifically for me, his memoir, Close to the Knives, was even more useful than his work as an artist (though many of his works also included narrative texts as well).

The Whitney has scheduled a Wojnarowicz retrospective for Summer 2018.

8. Robert Gober

Clearly, I am not the only one training his focus on Romantic Conceptualism of the early 1990s. The Gober retrospective at MoMA was achingly beautiful, and the climax of the exhibition, Untitled, 1992, blew me away.

4. Wolfgang Tillmans

I saw Tillmans perform with his new band, Fragile, at Union Pool in Williamsburg; it was incredible to see him take such an enormous risk, now that he is so widely known and commercially successful. He improvised on stage and really had fun with the performance. So inspiring to see such a well-established artist put himself out there and just do what he thinks might be fun and interesting without regard for what the consequences might be.

In Berlin, I met Tillmans at his project space, Between Bridges on Keithstrasse, during an the opening reception of “Playback Room, Part II: American Producers,” where I found myself seated in an audience-like group of chairs facing a massive set of speakers and an extremely professional turntable system. I was sitting alongside a bunch of very fashionable Berlin art viewers, all of whom were seated silently contemplating as if at the opera, but instead it was Missy Elliott’s Get Your Freak On, which was playing in all the incredible usually unheard complexity as it comes directly from the producers’ studio before it is dumbed down for radio and mass consumption. The project exposed the aural complexity of these popular tracks. Was it art? Tillmans didn’t give a shit, it was something he was interested in, so he made it happen, including renting (or buying) a set of really, really expensive speakers.

I was deeply moved by his last exhibition, particularly by one piece, a straight-down photograph of a box containing countless bottles of antiretroviral medication to treat HIV bearing his own name. Tillmans has been a touchstone for me — for possibly every young gay artist in the world — since the 90s, but this show at Zwirner was so good.

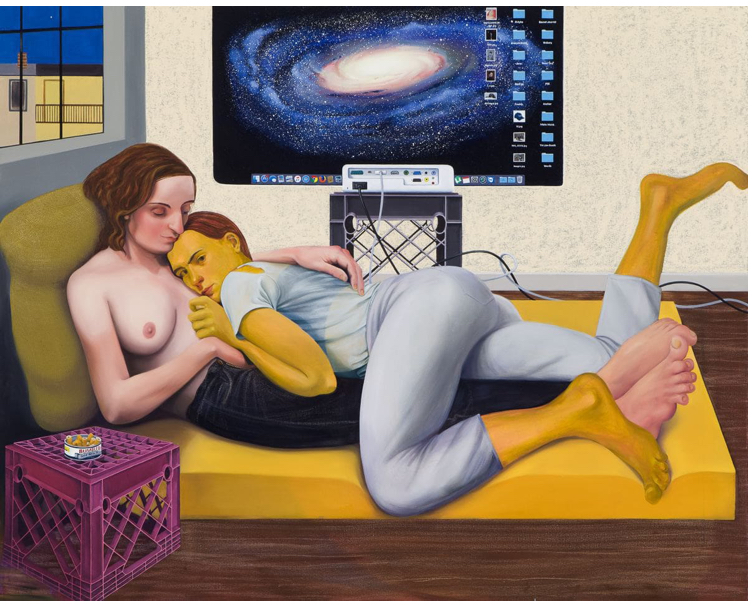

5. Nicole Eisenman

Nicole Eisenman, Anton Kern, May 19 – June 25, 2016

Nicole Eisenman, Al-ugh-ories, New Museum, May 4 – June 26, 2016

While it is so trite to say that current events that have no bearing whatsoever on your personal life have affected you, the mass murder that happened in Orlando had a profound effect on me. I decided that it was extremely important for me to directly address my identity and experience with my work as an artist. Eisenman’s show was up at the exact same time. It took on a very different meaning after Orlando. I wrote on this in The Brooklyn Rail:

Juxtaposed with the moments of incredible intimacy — trust within the group, being out-and-proud queer — recent events recontextualize these images: suddenly, we fear they contain something that would incite someone else, a stranger, to violence As much progress has been made, as complacent as we are living in a major metropolis (where being queer(4) is largely unremarkable), Eisenman’s portrayal of her personal life becomes a statement of continuing political urgency right now, in the wake of trauma.

In his “Commencement Address” for Parsons at The New School (Fine Arts BFA, School of Art, Media, and Technolog May 19, 2016), Gordon Hall said:

Queerness is, in my view, an approach to ourselves and one another that makes the bare minimum of assumptions about our own and one another’s bodies, self-conceptions, and trajectories. It is the willful cultivation of our ability to keep ourselves open to the simple fact that everything, and everyone, changes.

William J. Simmons’ letter to the editor at Hyperallergic

I am writing with regard to “A Truly Great Artist,” John Yau’s June 5 review of Nicole Eisenman’s exhibitions at Anton Kern and the New Museum. I have had the honor of writing in these pages myself, so I hope that this letter is understood as a respectful intervention. Hyperallergic remains one of very few publications that actively and unabashedly contends with identity politics in an allegedly “post-identity” climate.

It is for this reason that Mr. Yau’s review is disturbing, since it is something that I would expect to find in a more normative context. Yau suggests that Eisenman’s shift toward more recognizably “art historical” imagery was a positive step for her, “In making these changes, Eisenman moved away from an “us vs. them” world-view, which was true of much of her work in the nineties, to one that is infinitely more personal and nuanced. Why have we forgotten about Eisenman’s earlier work? Or are we repressing it because it’s too discernably lesbian? Do ink drawings of girl bars not appeal to us, as paintings that “look like” Impressionist urban scenes might?…

6. Jutta Koether

Jutta has the ability to imbue paintings with external political meaning through their installation and context. Additionally, she’s not afraid to take on messy, complex topics like mythology, the four seasons, love, and eroticism. Jutta and I recently met to discuss Francis Bacon and his ongoing impact on both of our work; Bacon’s raw emotional energy and his ability to make the erotic horrifying and vice verse was important to us both. Indeed, Jutta has made a number of paintings after Bacon.

Jutta employs painting as an apparatus in a larger conceptual program of performance, installation, just one of many components to create meaning. By training a light taken from a specific nightclub in New York which was active during the AIDS crisis on one of her paintings, it became an overtly political rather than merely aesthetic statement. David Joselit clarifies these kind of conceptual acrobatics in my all-time favorite theoretical text on painting, “Painting Beside Itself,” which revolves around a single exhibition at Reena Spaulings. Her steadfast commitment to her practice, and the fact that her story is now such a huge success, is deeply inspiring to me.

David Joselit “Painting Beside Itself.” October Magazine. Fall 2009, No. 130, Pages 125-134.

Jutta Koether, Zodiac Nudes, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin, September 16 – October 22.

Jutta Koether, Best of Studios at Campoli Presti, London, October 8 – November 12, 2016.

7. Francis Bacon

The picture of two men — either lovers or wrestlers (indeed, Bacon’s use of photographic source material, including images of men wrestling, is widely documented) together in bed (or a slab) as an intensely violent event. Bacon uses architecture and empty space to create an emotional tone for the figures.

Bacon was one of the first artists to openly portray erotic scenes of gay men, rather than shielding it through metaphors like boxing (George Bellows’ Stag at Sharkey�s, 1909) and swimming/sunbathing (Thomas Eakins, The Swimming Hole, 1884-1885).

9. Roland Barthes: A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments

Barthes, Roland. A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments. Translated by Richard Howard. Hill and Wang, New York, 1979.

Am I in love? “ Yes, since I’m waiting. The other never waits. Sometimes I want to play the part of the one who doesn’t wait; I try to busy myself elsewhere, to arrive late; but I always lose at this game: whatever I do, I find myself there, with nothing to do, punctual, even ahead of time. The lover’s fatal identity is precisely: I am the one who waits. (page 40)

The deep, extremely specific analysis of one of the most embarrassing states of mind: being depressed and anxious after a breakup, the revelation of finding out that your love is unrequited. The subject of so very many pop songs, but rarely the subject of a contemporary artwork, much less critical theory or philosophy.

11. Suzanne Joinson Joinson, Suzanne. “Hotel Melancholia.” Aeon, June 8, 2015.

“There is a part of the brain called the hippocampus that is shaped just like a seahorse. It is in many ways still an unconquered mystery, but it is believed to act as an internal sat-nav. It provides a crossroads between memory and the processing of location, and not just locations of geography and place — although it does deal in those, contextualising landmark objects and images to understand landscapes, interiors and scenes — but also the mapping of an emotional geography such as future goals and aspirations and how to reach them, or memory sequences, or the systemisation of our own personal narratives. It is how we understand where we are and how we put ourselves into the points of view of others.”

This entire text resonated with me, and I kept rereading it throughout the process of making this show. Particularly, creating a “crossroads between memory and the processing of location,” and “the systemization of our own personal narratives,” are central to my ongoing projects.

“Stephen Truax: How Will I Know,“ curated by Dr. Anne Luther. 67, LES, New York, NY. October 7 through October 29, 2016. Note: The gallery is open by appointment only.

Related posts:

Artists as curators: Stephen Truax

The donut muffin: Uniting two worlds

In praise of ‘Eating ass’. Line comparable to Degas, with the flair of Lautrec. The subtle pencil marks of Morandi. A subject matter Plato was not capable of confronting. And the thought of eating feces is as delightful as a picnic in spring. Continue to go forth artist and speak of higher truths. I await more enlightenment.