Contributed by Torey Akers / Allison Schulnik�s current solo show at ZieherSmith, “Hoof II,” posits personal mythology as a material condition for world-building. Each heavily impastoed piece functions simultaneously as portal and detonation site, issuing a challenge to the institutional semantics framing femininity in contemporary art dialogue. “Hoof II” expands Schulnik�s long-standing fascination with female protagonists in painting. (Note the cheeky titular reference to centaurides and unicorns, which is continued throughout the series in the names of individuals works.) Schulnik harnesses the telos of visual rhythm stroke by stroke, gesture by variegated gesture, and the results bespeak a praxis of vulnerability at times rending in its tragicomic earnesty.

The large, dark painting nearest to the gallery entrance is called Lady, and its haunting dignity casts a shadow over the space. Schulnik embraces historical allusion with the same brandishing, frowzy flourish she applies to the medium itself; the Lady pictured blooms in thick, chaotic swathes from her grounding void, recalling references as disparate as Ivan Albright and Waterhouse�s Ophelia. Like most of Schulnik�s oeuvre, this self-portrait elevates cumulative figurative technique to the stuff of identity construction � her subject matter mirrors oil�s dichotomous relationship with universal semiotics. Each painting in the show locates its viewer within the reverb of hypnotic, bodily echo, and Lady definitely shares in that dynamic. Her glassy, textured eyes stare past us with all the haggard intensity of an El Greco idol, wraith-like, floating slowly through the muck of painterly signification. The politics of meat and armor meld into something far weirder than a straight-forward feminist critique. Schulnik�s paintings re-imagine personhood itself as a process of accrual and approximation, carnal, stupid, and brutally meticulous in the attempt.

Even more fascinating than Schulnik�s relief-mottled character studies are their backdrops. The artist invokes high Renaissance portrait traditions with her use of activated depth, but rather than shy away from warm black�s more flattening properties, she leans in hard, icing her substrates with coats of umber-tinged sludge that stutter, clump, and skip forth from their requisite supports. That parodist�s attitude towards negative composition manifests similarly in works like in Purple and Red Flower, where blossoms resembling tumescent growths sprout from dense, lateral sludge, imbuing traditional image with a distinctly sculptural sensibility. Centaurette Cup, a small painting rendered in warm, crisp ivories and decorous blues, achieves Summer Wheat levels of oozing accretion. Lady�s sister piece, Gin #13, hung prominently to Cup�s left, features a woman holding a housecat aloft in cartoonishly chiaroscuro lighting. Its faux-religiosity bespeaks more than humor, however. Schulnik�s yearning for belonging is palpable, but her awareness of canonical exclusion�s political consequences intersects with that desire in stunningly tender swats at subversion. By queering compositional hierarchies through affect, Schulnik hits a fragile equilibrium – fraught, certainly, but satisfying in its psychic transmission.

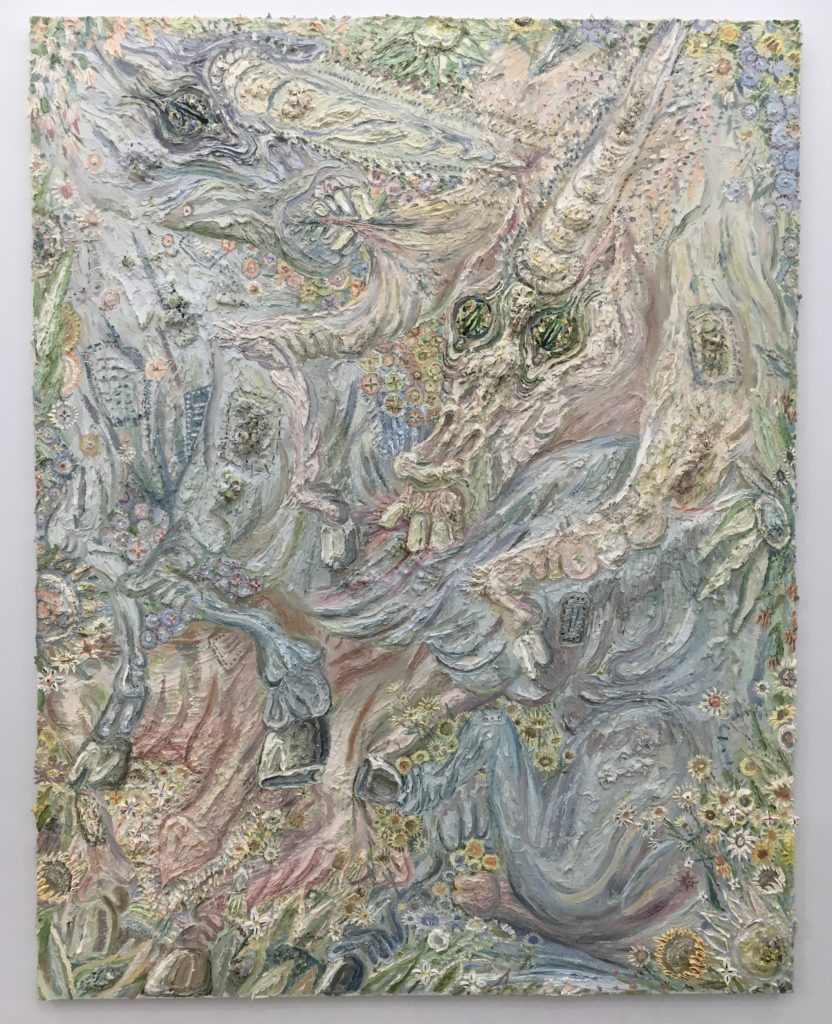

Two Long Unicorns pushes that ambivalence into overdrive. This manic flurry depicts creatures renowned for their innocence mauling at each other�s flesh in a field of daisies. Schulnik�s animals come across as frenzied, snaggle-toothed, bloodthirsty, even. Their chalky bodies intertwine in zany, fresh antagonism, a far cry from typical associations with tapestries and tween trapper-keepers. Just a few feet away, a modestly scaled, dreamy gouache portrays a girl-centaur gazing into the distance. Pink Centaurette displays little of the hyper-sexuality Ovid and company have ascribed to her kind in past texts. Instead, she appears wistful, serene, and possessed of interiority more human than beastly.

Schulnik employs a casual hand to problematize her more equine narratives, challenging onlookers to interrogate their own preconceived notions on the monstrous feminine. It�s that signature specificity that frees Schulnik�s pieces from any lingering didacticism; she maps the trauma of misunderstanding and embodiment�s encumbrance in paint, never fussing over the contradictory routes her material might demand. Believability takes precedence over politic, and that space, murky as it sounds, is where Schulnik�s work grows wings – ahem, hooves.

“Allison Schulnik: Hoof II,” curated by Andrea and Scott Zieher. ZieherSmith, Chelsea, New York, NY. Through October 8, 2016.

About the author: Torey Akers is a Massachusetts native and 2016 graduate of the MFA program at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. She earned her Bachelor�s Degree in English Literature from Northwestern University in 2011.

Related posts:

The stories we tell: Four paintings at Regina Rex

�Unapologetically carnal and verging on the grotesque�

Wow. Just….wow. That is the biggest bowl of semantic gobbledygook I’ve read since leaving grad school. Well done.

Scott,think about the words for a while. Maybe, like poetry, the meaning will reveal itself to you. I like the phrase “semantic gobbledygook,” but I’m actually more impressed with this interpretation of Schulnik’s paintings.

I don’t need a lesson in poetic metaphysics or any other such nonsense – and frankly I don’t think anyone being honest understands it either. I have an MFA just like anyone else and Ive dutifully read Habermas and Derrida, and I am of the mind of Baudrillard who said of French PostModern Theory (the ‘semantic gobbledygook’ to which I refer) “Nobody needs French theory”. Furthermore, it is not the job of the critic to further engulf already complex work with even more complexity through the liberal application of ridiculous semantics- that is neither explication, nor explanation and frankly is little more than intellectual masturbation for the ego deficient. I further assert that even Shulnik herself would find this sort of thing tiring as one must ponder who the hell has time to come to such twisted conclusions of their own process in the first place? Am I really to think that Shulnik, standing in her studio in front of a blank canvas, thought to herself “I will invoke high Renaissance portrait traditions by activating depth, but rather than shy away from warm black�s more flattening properties, I will lean in hard, icing my substrates with coats of umber-tinged sludge that stutter, clump, and skip forth from their requisite supports.” – let’s be honest, that is a sentence that started out with one theory only to unravel itself into contradiction, and it’s not the only example. The work definitely inspires one to think about numerous issues of contemporary painting, but there’s due consideration, and then there’s flights of fancy. There’s an excellent interview from Broadly by Olivia Parkes that does in the same number of words what this author could not, which was to enlighten the interested about the artists work in clear, straightforward language that neither insults, nor patronizes the reader. Look it up Anonymous (I don’t believe that’s your real name either!)