Contributed by Will Fenstermaker / The vultus, a Latin word that has no equivalent in Indo-European languages or ancient Greek, is the face that lies latent behind every image of a person. In an essay titled �An Idea of Glory,� Giorgio Agamben wrote that the vultus �isn’t something that transcends the face: it is the revelation of the face in all of its nakedness, victory over character.�

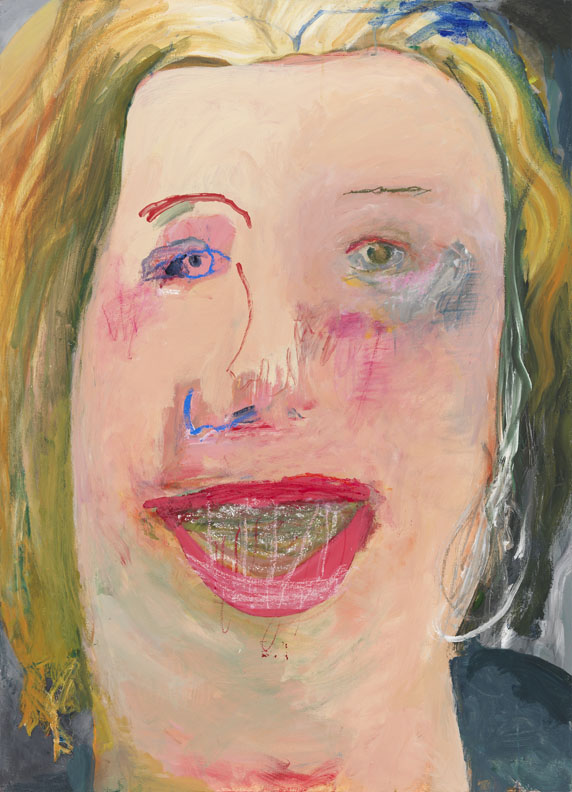

When I first saw Margot Bergman�s recent portraits at Anton Kern, I read them as fragments of conventionally realistic figures excavated from simplistic renderings. It seemed to me as though mature figures hidden behind the childish masks were breaking free–as if visible in amateurish marks were hints of a more classical talent, which required only Bergman�s hand to draw them out.

In fact, the faces Bergman paints are the profane ones, and they�re not amateurish at all. For most of the paintings in her first New York exhibition, the artist�s process began when she rescued paintings from flea markets and thrift stores. They sat in her studio, untouched for a time, because she struggled to decide what she wanted to do to them. Ultimately, she entered into a dialogue that would render the anonymous artists� hands all but unseen, except for selective fragments: piercing eyes perched in the middle of the new figure�s forehead, tender lips appearing where one might expect a nose, the signature of a painter named �Provol,� the aged and faded colors that peek out the sides of the frames. In Wilma Rose, for example, Bergman has deftly adapted the palette of yellows, greens, and blues that sculpt an elderly woman�s face. In her own way, the artist has faithfully reproduced the subject�s drooping eye, but the lips spread garishly, as if exaggerated by time. Gloria Jean�s deep-set eyes jump forward, yet a heavy eye-line establishes a melancholic shroud.

These portraits trick you into looking twice, and on second glance reveal a truer face. The found paintings are like those my great aunt might make. As her mind has begun to fail, she has taken up painting, with a great degree of talent. She gives her precious studies to family members�sparrows perched outside her window and, like Manet, the bouquets we bring when we visit. I imagine that when she paints our family, she�s crafting impressions to outlast the images she harbors in memory.

Of course I understand why Bergman is hesitant to erase such paintings, which might never have been intended as art, and rather exist only as family artifacts. But the overlaid faces she creates honor those beneath. Bergman paints these seemingly-rudimentary figures over realistic portraits as a way of �responding to the original paintings,� to draw out and exaggerate a raw element of personhood from each humble rendering. �Was not language given to us so that we might liberate things from their images,� Agamben writes, �giving appearance to appearance itself?� Such an ideal is achievable in painting too. In Bergman�s portraits she forgoes mere appearance. A vultus is a true face, not in the sense that it is the most realistic depiction, but in that it manifests only as a mask of the internal�fleetingly, whimsically, unrecognizably, it appears grossly distorted but colored by a sense of familiarity. As if the face has been hollowed out and repainted using what lies within.

“Margot Bergman,” Anton Kern, Chelsea, New York, NY. Extended through August 26, 2016.

About the author: Will Fenstermaker recently received his MFA in art criticism & writing from the School of Visual Arts, while working at the Guggenheim Museum in publishing & digital media. Before becoming a writer, he was an investigator for the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia.

Related posts:

Miami, Part IV: Rebecca Morgan�s eye on the figurative (and a bit of abstraction)

New British Painting in Helsinki: Figurative, modest, and miniature

Cheat sheet: Summer group shows (and what curators are writing about them)