Contributed by Jonathan Stevenson / In 2025, movies seemed to catch up with and confront the Trump era. Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another – based on Thomas Pynchon’s novel Vineland and nimbly arraying multiple stars with Leonardo DiCaprio in the lead – is a deeply informed outcry of conscience and resistance, chiseled by satire into a grand statement. Bugonia, Yorgos Lanthimos’ creepily penetrating and funny…

Latest articles

Sally Gall: What am I looking at?

Contributed by Leslie Wayne / I recently had the pleasure of visiting the artist Sally Gall in her midtown studio on a cold and snowy day – a perfect opportunity to get out of my own head and into the mind and process of someone else. Gall is a photographer of natural phenomena, yet her images are otherworldly and hard to identify. They include close-up undersides of laundry hanging from clotheslines on a windy day, faraway kites, and rock faces that look like Franz Kline paintings.

Mira Schor: Uncensored

Contributed by Jonah James Romm / How does one acquire language? How do words shape identity and meaning? These questions might strike you upon entering Mira Schor’s exhibition “Figures of Speech” at Lyles & King. Bringing together a previously unseen body of the artist’s work from the 1980s and paintings from the last two years, the exhibition traces the compelling self-referential progression of Schor’s work over the last four decades.

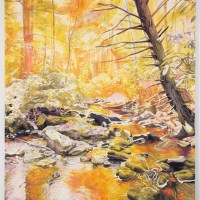

Two Coats Resident Artist: Nichole van Beek, March 16–20

Contributed by Sharon Butler / This month, Two Coats of Paint is glad to welcome Nichole van Beek to the Residency Program, from March 16–20. For a show at the Morris N. Flecker Memorial Gallery in 2017, when she still lived and worked in NYC, Matthew Neil Gehring aptly introduced her paintings as “macrocosmic encounters with impossible and tantalizing illusions situated in a space that is once grounded in the familiar, the natural, yet is infinitely expansive.” She moved from NYC to the hollows of the Appalachian Mountains several years ago and found new content and media for her art practice, but she has retained the fine balance Gehring described between the big picture and smaller ones.

Tappeto Volante’s rich conversations

Contributed by Jonathan Agin / The fifth annual “La Banda” show at Tappeto Volante Projects in Gowanus features relatively new paintings, sculptures, and works on paper by over three dozen mostly local artists. Though no designated theme governs the show, it was forged in the pandemic era and celebrates New York’s creative and communal spirit. Populating a cozy space with such a density of art practices can’t help but generate new discourses across mediums, subjects, and generations.

Kate Hargrave: Unsettling and generous

Contributed by Lore Heller / “MILK TEETH,” the title of Kate Hargrave’s show at Karma, implies both permanent loss and permanent gain. One gains milk teeth as a baby and loses them as adult teeth take their place. If children place them under their pillows, fairies might bring rewards. Losing milk teeth is losing childhood, developing permanent teeth coming of age – reminders to parents that time inexorably arcs life. Joni Mitchell observed that “we’re captive on the carousel of time,” and my grandmother’s lullaby, “toyland, toyland, beautiful boy and girl land,” reminds us that “once you cross its borders you may never return again.” Hargrave, who painted this work as she raised two children, captures this pervasively bittersweet quality.

Felix Beaudry’s malleable boys

Contributed by Bill Arning / There is something wildly compelling when an installation flips on you—reversing itself in meaning and affect if you linger more than five minutes. Felix Beaudry’s “Malleable Boys” at Situations is one of those shows. On first entry, oversized, lumpy, monstrous heads loom and encircle you like funhouse demons. They feel nightmarish—deformed, melting, mid-metamorphosis into dangerous humanoid creatures. But stay a beat longer and the menace softens. They become almost cute, like huggable, overgrown Cabbage Patch Kids—less terrifying than misunderstood.

Araujo, Greenberg, and Simon at Ptolemy

On the occasion of their exhibition, “Artist Panel,” at Ptolemy, Two Coats of Paint invited Michele Araujo, Larry Greenberg, and Adam Simon to share part of their conversation with gallery owner Pat Reynolds.The following transcript has been edited for length and clarity, but the full conversation will be playing at the gallery through March 15, 2025.

NYC Selected Gallery Guide, March 2026

I was doing an artists talk with Jason Travers at 68 Prince Street Gallery in Kingston, NY, two weeks ago, and the subject of politics came up. Jason said he kept going back to sinking ship analogies. “It’s sometimes lost that even on the sinking Titanic there was hope for humanity. While it was sinking, there was a string quartet playing for panicked passengers. These musicians kept playing while the ship went down. The man who led that quartet was Wallace Hartley. I don’t want his name to be forgotten. There was a time when I would think about him and feel angry— why are you playing music when you should be getting on one of those boats? Now I look back at his contribution differently, and I do think it was a contribution. He was doing the only thing he could do. He was restoring a sense of humanity at the moment it was most needed — even if no one was listening. In a way, that’s the analogy for the artist today. I feel like Wallace Hartley — playing music while the whole world is falling apart and nobody’s paying attention.”

Hudson Valley (+ Vicinity) Selected Gallery Guide, March 2026

Contributed by Karlyn Benson / Hudson Valley residents have been eagerly awaiting March and it’s promise of milder weather. With longer days come exciting new exhibitions throughout the region. On March 7, SPIRIT IN THE FLESH: Courtney Puckett, Ben Pederson, and Saul Chernick opens at Utopia in Kingston, The Dark Abyss of Time opens at Holland Tunnel Revisited in Newburgh, and solo shows by Daniel Giordano, Davana Robedee, and Kathy Ruttenberg open at CAS in Livingston Manor….

Pinkney Herbert: Unsettled

Contributed by Paul Behnke / Pinkney Herbert’s exhibition “In Between” at David Lusk Gallery regards a painting less as a finished image than something unfolding in time. The title points to a place of transition where matters are not fully settled but are still taking shape. Herbert has long divided his time between Memphis and New York, and itineracy seems to carry into the work. Structure, rhythm, color, and pace energize paintings that never completely resolve. Across the exhibition, Herbert denies the viewer a stable place to land. Lines shift direction, forms collide, and constructs loosen almost as soon as they appear.

Wifredo Lam’s global reach

Contributed by Margaret McCann / “When I Don’t Sleep I Dream” at the Museum of Modern Art traces the odyssey of Afro-Asian Cuban painter Wilfredo Lam (1902–1982). His 20th-century oeuvre encompasses a prescient global combination of influences. Youthful talent afforded him portraiture study in Spain, where he remained for 15 years. But, like Goya, inclination and events pushed his art past appearances.

Reaching back at Ruthann

Contributed by Natasha Sweeten / I thought of this quote as I viewed “Souvenir,” the current group show at Ruthann. Inspired by a poem of the same title by Edna St. Vincent Millay, the show brings together the work of 15 artists with a focus on moments “that touch on intimacy and affection, humor and sadness, absence, and memory.” That’s quite a bit of ground to cover, but for me – no doubt influenced by reading the poem posted on the gallery wall – the prevailing theme is memory and the emotional aftermath of happier times. As Joni Mitchell famously sang, you don’t know what you got ‘til it’s gone.

Jenny Lynn McNutt: Nativity of squirms

Contributed by Jason Andrew / At the New York Studio School Gallery, Jenny Lynn McNutt’s exhibition “Touch Me” reclaims figuration in ceramics as a matter of urgency rather than nostalgia. With an immediacy that heightens their corporeal impact, McNutt kneads together cultures and rituals embraced during her travels to West Africa, China, Eastern Europe, Ireland and Italy. The 20 sculptures representing a decade of work embody forms twisting, crouching, bracing, and blooming in what the artist aptly describes as “a nativity of squirms,” which captures both their generative vitality and their refusal of repose.

Polly Shindler’s natural reverie

Contributed by Lawre Stone / Known for painting interior spaces and domestic objects, Polly Shindler shifts her subject to the rural Hudson Valley landscape for her exhibition “Valley Music” at Deanna Evans Projects. Images of mountains, flowers, and fields hang in sequence on the walls, like a roll of snapshots taken from the car window. Shindler’s paintings do speak to the compulsion to pull over to the side of the road, take out the phone, and hope to capture the elusive, astonishing beauty of nature. Complementing the landscapes are larger, close-up paintings combining flower heads, stems, and leaves with abstract elements. Schindler’s flowers grow from the ground, with wispy stems and simplified blooms reaching for otherworldly skies. Painting in a full Crayola color array, she plumbs the sublimeness available every day.