Contributed by Dion Kliner / Looking from painting to painting at “The Course of a Distant Empire,� Jay Senetchko�s fine solo exhibition at Windsor Gallery in Vancouver,�you might begin to recall�the distinctly dissonant percussion in�Tom Waits�s cheerfully ominous�song as he plaintively asks, �What�s he building in there?� And then, �Where in its course does this empire exist? In which direction is it moving?� How does Senetchko mean that direction to be understood? Do the paintings�-�The Fire Sermon,�A Game of Chess,�The Burial of the Dead,�Death by Water, and finally�What the Thunder Said�-�represent a state of falling from, or building towards? Is their message a pessimistic descent into a dark age, or an optimistic recovery from catastrophe and dawn of a bright and sustainable new future?

Having been a frequent visitor to the Catskills, when faced with a group of paintings that include both the words �course� and �empire,� I naturally think of Thomas Cole�s five-painting 1934 series, �The Course of Empire,� which illustrates an amalgamation of the two metaphors generally used to embody the concept of time�s passage (the arrow and the circle) through the story of a mythic empire. The�arrow captures the uniqueness and distinctive character of sequential events, while the�circle embodies�events as lawful, predictable, and recurrent phenomena. Cole�s empire has run its course from The Savage State, to The Arcadian or Pastoral State, to The Consummation of Empire, to Destruction, and finally to�Desolation. There�s no new beginning for this particular empire, but the cycle of rise and fall as applied to another will begin again. This �cyclical theory of history� (the one-way road from inception to decay to which�the theory suggests all nations are subject) informed�Cole�s empire, which in turn is an indispensable guide to Senetchko�s. A second guide is T.S. Eliot�s 1922 masterpiece, The Waste Land:�the individual titles of �The Course of a Distant Empire� also those�of the five sections of that poem, but reordered, says Senetchko, �to better reflect the paintings�s contents.�

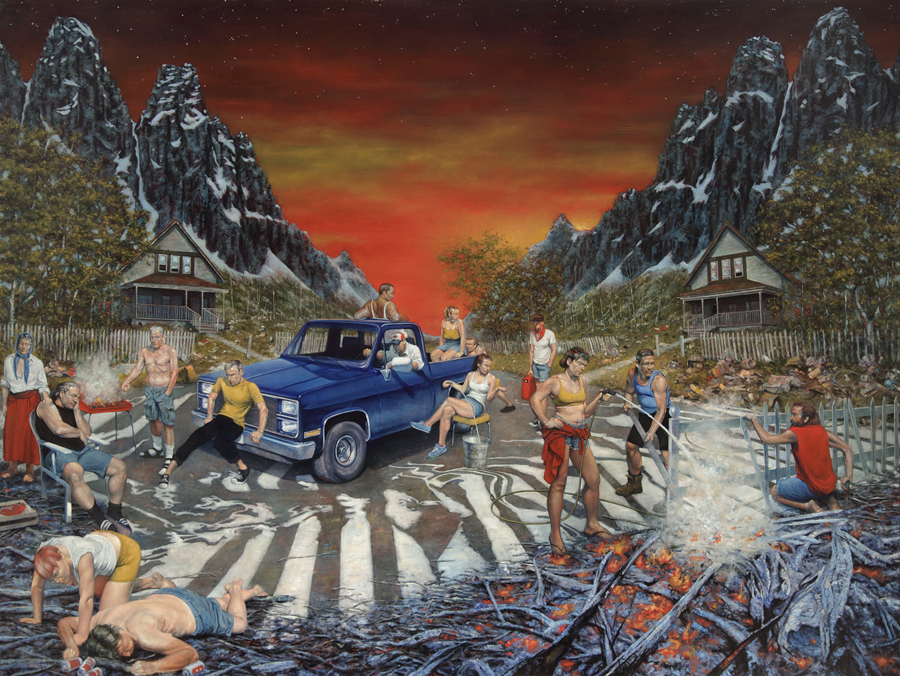

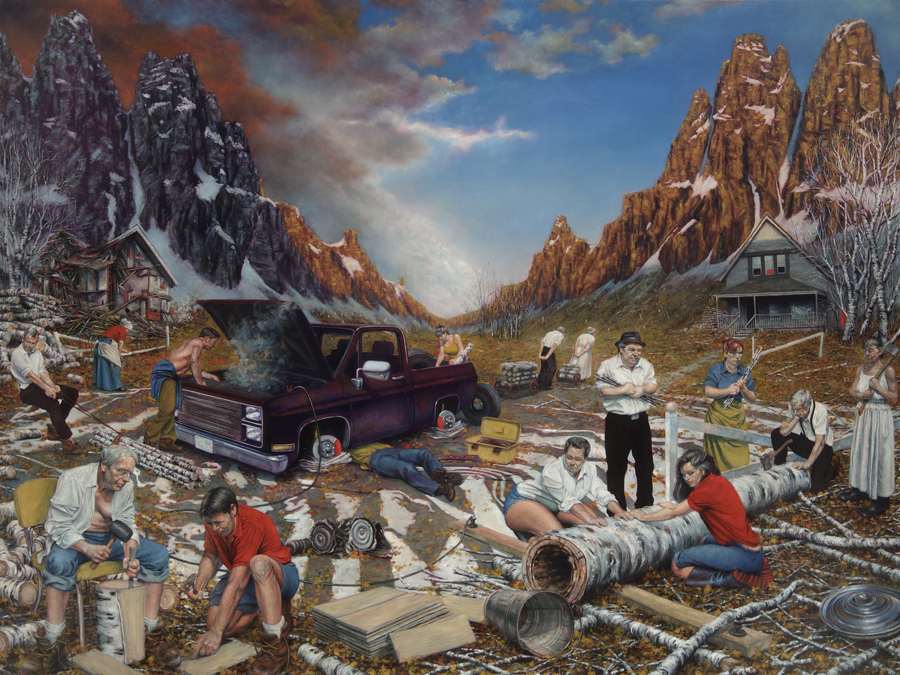

Cole painted the development of his empire from shifting viewpoints of a single locale in an expansive and sublime Hudson River School landscape. Senetchko has nailed his down to virtually a single point of view of a single location in a narrow valley that shows close bilateral symmetry (mountains, houses, trees, white picket fences), especially evident in The Fire Sermon. With its eerie orange sky and odd, disjointed activity, it�s reminiscent of the inside back cover of Mad magazines that could be folded to create a satirical comment on the unfolded image. Even in those paintings with less bilateral symmetry, the stability and balance have been assured by being laid out in compositions that form an X, with sharp and definite vanishing points in the distant crotch of the mountains at the very center of the canvasses.

If you place the two series side by side, it�s easy to imagine that The Fire Sermon begins in Desolation, as it were. It�s not that Senetchko�s characters are former residents of Cole�s mythic empire, but rather that they are survivors after a fall: call it catastrophe, apocalypse, or Destruction. To slyly assert the status of his characters as survivors of a traumatic event, Senetchko has matched their number to the number of survivors represented in G�ricault�s The Raft of the Medusa (fifteen), and repeated the painting�s placement of a dark-skinned figure atop a compositional pyramid. To refresh the memory, the primary pyramid of The Raft of the Medusa�is composed of bodies (mainly of the living) built on top of a raft. Together they strive desperately, their attention directed to the man at the apex who signals to a distant ship on the horizon. They hope for their salvation. At the lower left an older, white-haired man sits looking away dejectedly, perhaps figuring there�s no hope left. In The Fire Sermon it�s a dark skinned woman who�surmounts a compositional pyramid that includes the motionless truck. No one supports her. There is no striving together towards a common goal. There is no drama. Very little interest is paid to anything by anyone including the woman at the top, who, if she could be bothered to look towards the horizon, wouldn�t see anything anyway. At the lower left Senetchko also places a seated, older man who might be dejected if he weren�t busy napping.

Whatever brought these people to this state, by the time of The Fire Sermon any discernible sense of its threat or danger has vanished. There is no intimation of frustration, no particular sense of urgency to the action. Work seems to be carried out at a leisurely pace, the people secure and content enough to spend time relaxing, barbecuing, or getting drunk. From here they move forwards in their cycle by moving backwards into Cole�s: Senetchko�s What the Thunder Said meeting up with Cole�s The Arcadian or Pastoral State as representations of idyllic states and the regeneration of nature. This is as far as �The Course of a Distant Empire� goes. However, if visible signs of advanced technologies continue to disappear, taking with them the knowledge of how they work, the next step for Senetchko�s band of castaways is The Savage State.

The chronology of �The Course of Empire� unfolds in a unified and consistent way. Time moves at different rates, but in the same direction and with internal coherence. Its proceeds, from�inception to zenith to ruin, over the course of a day, sunrise to sunset. The landscape changes accordingly in proportion with the expansion and contraction of human development: land is cleared; architecture is built; architecture falls down; vegetation returns. In �The Course of a Distant Empire� time progresses at differing rates, in at least four different modes: seasonal; human; what I�ll call “material;” and geologic. Seasonal time moves logically through an entire cycle from summer to summer. Human time seems pretty well in synch in the first four paintings, in which�no noticeable aging occurs. Then, in What The Thunder Said, two adults (an old man and a young woman) are gone, replaced by the appearance of two children (a boy and girl). Maybe they�ve always been there out of the picture, or maybe we�ve suddenly skipped a half dozen years into the future. Materially, decades must pass: houses collapse and are rebuilt, the truck goes from new to a rusted hulk, and the paved area the truck sits on degrades enough that�a field of poppies appears. Finally, look at the mountains, check their contour from painting to painting: they change. Not because of the relative position of the spectator, and not the passage of eons. The changes aren�t chronologically coherent, the contours fluctuate between being sharper, hence geologically younger, and older and more worn. These inconsistencies in time are disorienting and create rents in the contiguity of the spatial and temporal fabric we think we see. The implication is that the specifics of location, events, and character are unimportant to Senetchko. These mountains could just as well be any mountains; or they might be substituted (along with the rest of the valley) for a prairie or an eastern deciduous forest. The�small group of individuals that look the same from painting to painting are not meant to be the same individuals. They are the idea of �society� made intimate and personal. Activity looks largely haphazard and detached: even when in close proximity people don�t�seem to be �in real contact most of the time. They�also appear to have�paused from whatever they were doing, giving each scene the stillness of a museum diorama. The landscape is a backdrop in front of which stand-ins perform tableau vivant. Against the fluidity of time, Senetchko has positioned a�static mise-en-sc�ne.

The single example where the figures appear to be in motion and they work cohesively as a group is in the central painting, The Burial of the Dead (corresponding to Cole�s The Consummation of Empire). Here costume, tool, and activity are all coordinated and directed to a single task. Dark and hooded, the figures look like representations of Death. None of the faces are visible from within their hoods; the two we should be able to see into are empty and black. The one figure, arms crossed, leaning on its snow shovel, the one that looks to be fixing on us directly, looks particularly like an invocation of the everyman Reaper, sickle replaced by shovel.

This painting is also a good place to look at the two central images that, excluding landscape, are consistent throughout the paintings since so much else is obscured by snow: the truck and the �crosswalk.� The truck sits in the approximate center of an ellipse, like the epicenter of a blast, formed by a changing collection of characters and detritus and around which almost all activity revolves. In The Fire Sermon the truck looks to be in good condition and a focus of interest. Then, over the course of what looks like a year, it is slowly stripped and crumples, until by What the Thunder Said it�s a barely recognizable repository for flowers. As representative of advanced technology, its total loss could be troubling. Below the truck is a section of asphalt, the remains of what once was a road, or more likely a cul-de-sac. Most of the section we see is painted with white bars that suggest a crosswalk, but the lines recede too deeply, and whether it ever had utility is questionable. As it stands, it looks like a meaningless, functionless bit of artificially imposed human structure overlaying the world beneath, but to the people in the paintings it seems particularly meaningful since it�s the only area that concentrates all of their attention and activity simultaneously. The further away they move from the truck the more regular and consistent they are. Close by, the white bars appear liquid, as if they�re in a state of arrested flow, or radiating out from a center like ripples after a stone is dropped into water, or reflections in a funhouse mirror. They change from painting to painting, but they persist no matter what changes occur to the surface below: maybe because in Death by Water it looks like a jig is being made to refresh them. If it�s not a crosswalk, why plant the misleading suggestion of one? Arguably the most famous crosswalk, if not only in the collective Western memory, then in the world, is the one the Beatles are crossing on the cover of Abbey Road. As the last album to be recorded by the Beatles it signified a change in culture, and its cover supposedly contained the clues to the death of Paul. In Senetchko�s scheme, perhaps the crosswalk retains its importance to its characters as a remnant of cultural memory that is eventually lost (like the technological know-how lost with the truck) under a memorial carpet of poppies.

Of the many references to visual culture besides Gericault embedded in �The Course of a Distant Empire,� two others are most striking. Found amongst the women dressed in contemporary clothing are several that wear what look like archaic peasant costumes, including headscarf. Two are taken directly from Millet�s Gleaners, but shown as mirror images: the Gleaners�s half-bent figure on the right, is in the left middle ground of A Game of Chess; and the Gleaners�s central figure, is middle ground just right of center in Death by Water. Continuing the peasant theme, but in a less direct manner, are references to the paintings of Malevich. Before and after the Suprematist paintings for which he is best known, Malevich painted series of peasants (even the title of the Suprematist painting commonly known as Red Square was titled by Malevich as, Painterly Realism: A Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions). Their palette is predominantly red, black, white, blue, and mustard yellow, used as flat areas of color (which he carried over into the Suprematist work). Senetchko has used the same palette in all of the clothes, and in many other objects, with very little variation in hue from one usage to the next. So, for instance, in A Game of Chess the same yellow that is worn by the three figures around the truck is also worn by a woman collecting twigs, and is the color of a toolbox, seat cushions, and an indicator light on the truck. The same red worn by three other figures is the same as the soles of rain boots, the brake shoes of the truck, and seen as a rectangle in the center upstairs window of the house on the right. And it�s there in the windows that Malevich�s iconic Suprematist compositions with squares and rectangles are referenced: including the Black Square, Red Square, and Painterly Realism of a Boy with a Knapsack – Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension that shows a black and red square on a white ground. From the point of view of an artist, it�s easy to understand why Senetchko would want the work of Gericault, Millet, and Malevich to be remembered. Their work is important to him, it�s where he comes from as a painter. What makes peasants significant is harder to gauge. Within the paintings they read like portents for the direction and ultimate destination for this group of fictional characters. For we the living, they could be an inducement to remember this way of life as a possible future face of a form of sustainable social organization. And for Senetchko they represent not just cultural history and social history, but personal history too. Senetchko�s heritage is Ukrainian, his forbearers farmers. Malevich, though considered a Russian artist, was born in what was the Kiev Governorate (now Ukraine) and referred to himself as Ukrainian, so he and Senetchko are landsmen.

Cole�s �Empire� has been described as encapsulating both his pessimistic view of history, and a thinly disguised critique of Jacksonian democracy in America. Pessimistic it may be, but it�s only a cautionary tale, a dire prediction of what could happen to America. At the time, Cole and his contemporaries weren�t sure where America was in the cycle, and wondered whether American democracy and �improvement� might actually effectuate an escape. Eliot, on the other hand, felt he knew where the culture around him was: on the way to hell in a hand basket. He wrote The Waste Land in part as a lament about his feelings that the cultural empire around him was in the decline and fall stage of the cycle. Nevertheless, he filled it with classical references that would have been obscure at best to all but his most astute readers. In place of the dumbing down Eliot felt he was witnessing, he wanted to substitute dragging people up. His inclusion of references carries a fundamental message, the same, I believe, as Senetchko�s, �you should not forget this,� or, in a slight, but importantly different formulation, �don�t forget from where you come.�

As a distinct and unifying metaphor every painting of �The Course of a Distant Empire� has occurrences of the ignition and extinguishing of fire: the symbol extraordinaire of human development, ingenuity, and imagination. In the end, does it stay lit or go out? The truth of the pessimism Cole put into �The Course of Empire� is that it was due in large measure to his antipathy towards the destruction that was just then beginning of the pristine landscape he loved, and the scourge of industrial development. And he was in no way averse to the idea of a return to the kind of simpler, pre-industrial world that he forecast. Could the �Distant Empire� represent a hoped for communal and agrarian emergence from our present crises? Does Senetchko, like Cole, entertain the possibility of escape into a perpetual idyll? I don�t think so.

It looks like Senetchko shares Cole and Eliot�s pessimism, but he�s painted it without the tragedy and drama of epic. Senetchko�s empire doesn�t so much rise and fall, as amble aimlessly along in a land where Newton�s Third Law (For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction) descends to slapstick: a perfect example in The Fire Sermon, where two men push the truck in opposite directions unaware of what the other is doing. He�s represented his concerns for the loss of knowledge and culture, and the future of human action, interaction, and organization as a Beckettian state where willingness and pointlessness cancel one another out in apathy. In What the Thunder Said, the vanishing point shifts for the first time from above the distant mountains to whatever is in front of them at their base, and there is an indication of a flattened horizon that divides the painting in half: from the white picket fence on the left, across the roof of the truck, to the shape of the clump of trees, almost where the red of the poppies become indistinct. It gives compositional form to an expression of lowered expectations, and the giant X of the compositions can be seen as a giant and cautionary, �Please, not this. There�s no kinda Gericault or Eliot gonna show up on this horizon.�

——

About the author:�Dion Kliner�is a Vancouver-based sculptor and arts writer who has�published more than�forty reviews and catalog essays.

Related posts:

Nicole Eisenman and the triumph of painting

Lunchtime dystopia: CON-Figuration at Postmasters

New subjectivity: Figurative painting at Pratt Manhattan Gallery

New British Painting in Helsinki: Figurative, modest, and miniature