Contributed by�Elana Herzog�/ In January I spent a week in�Yogyakarta, Indonesia, on the island of Java, where I had a glimpse of a lively, burgeoning contemporary art scene. My guides were�Sally Smart, an Australian artist based in Melbourne and Yogyakarta, and�Entang Wiharso, an Indonesian artist based in Yogyakarta and Rhode Island. The city of Yogyakarta is home to quite a number of artists from the region, and is the location of�the�Indonesian�Institute the�of�Arts. It hosts YOS (Yogyakarta Open Studios) in October each year, and Art Jog, in May, both of which attract Arts professionals and collectors from all over the region. In addition to artists collectives opening up there studios and galleries hosting shows, these events feature programing and discussions with invited scholars and other professionals. Art Stage Jakarta, an art fair with a rising profile, takes place in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia�and�is an outgrowth of Art Stage Singapore.

Contributed by�Elana Herzog�/ In January I spent a week in�Yogyakarta, Indonesia, on the island of Java, where I had a glimpse of a lively, burgeoning contemporary art scene. My guides were�Sally Smart, an Australian artist based in Melbourne and Yogyakarta, and�Entang Wiharso, an Indonesian artist based in Yogyakarta and Rhode Island. The city of Yogyakarta is home to quite a number of artists from the region, and is the location of�the�Indonesian�Institute the�of�Arts. It hosts YOS (Yogyakarta Open Studios) in October each year, and Art Jog, in May, both of which attract Arts professionals and collectors from all over the region. In addition to artists collectives opening up there studios and galleries hosting shows, these events feature programing and discussions with invited scholars and other professionals. Art Stage Jakarta, an art fair with a rising profile, takes place in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia�and�is an outgrowth of Art Stage Singapore.

It was my first time in the region so much of what I saw was new to me. The country of Indonesia is an archipelago of over 17,000 volcanic islands of which, according to Wikipedia, 6,000 are inhabited. Due to it�s positioning, maritime trade has historically been a central part of the Indonesian economy.�Also agriculturally rich,�the location�has been a major coffee and tobacco producer. The image of the trading ship recurs in many traditional art forms. Indonesia�s history has included multiple invasions, conquests, migrations and internal political conflicts. The legacy of colonialism and military conflict was never far from my mind, and is a clear influence in the work of contemporary artists. Its population is diverse, and for many centuries Buddhist, Hindu and Muslim communities coexisted in relative peace.

It was my first time in the region so much of what I saw was new to me. The country of Indonesia is an archipelago of over 17,000 volcanic islands of which, according to Wikipedia, 6,000 are inhabited. Due to it�s positioning, maritime trade has historically been a central part of the Indonesian economy.�Also agriculturally rich,�the location�has been a major coffee and tobacco producer. The image of the trading ship recurs in many traditional art forms. Indonesia�s history has included multiple invasions, conquests, migrations and internal political conflicts. The legacy of colonialism and military conflict was never far from my mind, and is a clear influence in the work of contemporary artists. Its population is diverse, and for many centuries Buddhist, Hindu and Muslim communities coexisted in relative peace.

Arriving at my gate for the flight from Dubai to Jakarta one of the firs things I noticed was the of brilliant color of people�s clothing and headscarves, and the significant number of people wearing surgical facemarks. I was also struck by the sound of coughing in the airport and on the flight. It didn�t take long for me to realize that this probably wasn�t because it was flu season, but more likely a result of air pollution and cigarette smoke. Once in Yogyakarta I saw that motorbikes are the mainstay of how people get around, and the absence of sidewalks in the narrow streets discourages pedestrian traffic. The density of people and vehicles (both civilian and military) represented in much of the work I saw, makes perfect sense in the context of this tropical urban landscape.

At the�Sultan�s Palace

The Javanese Shadow Puppet Theatre, known as Wayang Kulit (Wayang is the Javanese word for shadow) is among the most visible traditional art forms, using an oral tradition to sustain cultural narratives through performance. its influence on the contemporary art of the region is huge. Traditionally these performances, which may employ hundreds of puppets, multiple performers and singers, and an orchestra of gamelan players, might go on for 24 hours and more. The flat, hinged puppets, made from leather, are cut to form elaborately perforated silhouettes, with highly articulated edges. They cast dramatic shadows on a white screen when a light is projected from behind them. A trip to the Sultan�s Palace on a Saturday morning included a modified three hour Wayang Kulit performance.

Entang Wiharso

Our first studio visit was to Entang Wiharso, who lives with his wife Christine and their two sons in a complex of buildings surrounded by gardens, and flanked by rice fields. The studio houses several projects in progress, as well as completed works. Entang makes large scale painting, cast sculpture and wall reliefs. His work features dense compositions, in which human figures, often with long, lashing tongues, are intertwined with one another, with machines (mainly motor vehicles) and with animal forms, and. His hybridized imagery invokes both cyborg

Entang�s work will be the subject of his second show at Marc Strauss Gallery in New York City, opening in April 2017.

Wiharso: �I create visual narratives about ethical issues or problems � morality,�human acts, politics, loyalty, identity, technology, modernization vs. tradition � by creating�images that people identify with from mythology�..�..For example, depictions of the human tongue that transforms into a snake or fire refers to how the tongue is a powerful organ that can be used as a tool to create manifestos, influence, lies and propaganda; or the tip of the tongue turns into a crab leg to discuss clich�s about Indonesia as a nation of idlers who just talk and walk slowly; or the tip of the tongue turns into a hand holding�a knife to depict back stabbers or traitors.�

Sally Smart

Sally Smart�s large scale fabric collage installations have long featured maritime and pirate imagery, as well as references to Eastern and Western dance and puppet traditions, reinterpreting early twentieth century surrealist collage practices through a feminist lens. Smart has completed major works focused on the character of the female pirate, and is currently drawing inspiration from the Ballets Russes.

While maintaining a studio in Melbourne, which she has had for most of her career, Sally has recently opened a second studio in Jogjakarta. Here she produces some of her newest work, which are based on digital collages, with the help of professional embroiderers. In her studio I saw large appliqu� banner-like work in progress, as well as the latest of these embroidered pieces. Several of the embroideries were exhibited as part of her 2016�solo show ay Postmasters Gallery, in New York City.

44.5 x 39.4 inches.�DGTMB Art Embroidery, Yogyakarta

Smart: �I combine this process oriented practice of cutting, collage, photomontage, staining and pinning as methodologies integral to the conceptual unfolding of this work, and relating to femmage: a term created by the American feminist and theorist, Miriam Shapiro to describe her collage works and women�s historical connection to making including collage, photomontage and embroidery, linking to these political feminist origins���.The choreographer Martha Graham and Pina Bausch and the early modernist artists associated with performance, especially Hannah Hoch and Sonia Delaunay are important references to this work.�

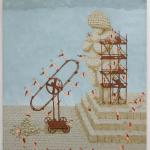

Heri Dono

Heri Dono is one of more senior and established of Yogyakarta’s contemporary artists. Our visit was hosted by Heri and his assistant Agni Saraswati who showed us several buildings housing many pieces, a library, and workshop spaces. While we were there a martial arts class was taking place in one part of the studio and attended by friends and members of the community.

Heri�s work was some of the most overtly political of the work I saw in Yogyakarta, delivering social critique with a his rye, whimsical, and somewhat dark, sense of humor. After all, Heri�s studio is named Kallahan Studio, after none other than Harry Callahan, (aka Dirty Harry,) Clint Eastwood�s signature character. His large sculptural installations include military paraphenalia, vehicles and hybrid human/non-human creatures, many with flashing lights and kinetic elements.

2001,�sheet metal, paint, hardware, dimensions variable.

Note:�The highlighted quotes are from�King, Natalie, “A Conversation with Entang Wiharso and Sally Smart,” Ocula, 20 January 2017.

About the author: Artist Elana Herzog has been the subject of museum surveys and solo exhibitions in over 20 cities in the U.S. (including her native New York City) and numerous cities in Europe. Her installations are characterized by a mix of rigorous hard work and playful, context-sensitive experimentation, in which the labor-intensive “making” (literally hundreds of hours of sheet-rock building, pneumatic stapling, ripping, shredding, and un-weaving) is ultimately subsumed into a final product that is so light-on-its-feet that it almost seems to dissolve.

Related posts:

The Pedagogical Puppet: Sally Smart explores time-based media

Justine Frischmann at VOLTA (and everything else)