In Suzanne Joelson‘s confrontational new paintings the conflicting forces of order and disruption animate a lively hash of vinyl photographic banners, paint, patterning, hollow-core wood panels, broken bits of debris, fabrics, geometric sequencing, and idiosyncratic markmaking. On the occasion of her solo show Studio 10 in Bushwick, Joelson met with painter Michele Araujo to talk about her new work.

Michele Araujo: I want to start by asking how you felt when you first saw the vinyl supermarket banners that you use in several of these paintings. There’s a shift between the use of the vinyl and the materials–fabric, netting, old clothes and objects–you used in the older paintings.

Suzanne Joelson: They seemed beautiful, but funny and repellent. Instant lust. Gary [Stephan] and I run along the Hudson past the World Trade Center where there was a construction site for a new food market, covered with graphics resembling old barns and images of the all food that was to come. At the time I was using old plywood in my work, and I liked repeating the wood grain with a cartoon version. The hyper wood grain and the photographic quality of these graphics was completely different. A spectacle of tomorrow’s groceries. After about a year Gary noticed that one of the graphics was in the trash. We ran home carrying the filthy vinyl, feeling like thieves. The next day I spoke to the construction manager who agreed to call me when they took down the rest.

MA: There’s a difference between the vinyl banners–they have printed images–and the materials you’ve used in the past.

SJ: When I got the vinyl home I saw how wackily out of scale the images were with what I was doing. The scale and the photographic quality inspired me to work in a different way. The discarded remnants of wood grain were frayed and patched with a mismatched sample. The repatching reminded me of the Rustem Pasha Mosque in Istanbul which has been a major source of inspiration for over a decade. The mosque has a profound arrangement of beautiful iznik tiles and on one door they were replaced in a complete jumble that had little sense of the original order.

Something about a system breaking down and then emerging had been part of my thinking for awhile. The stained glass windows of the Winchester Cathedral are another example. After the bombing in WWII they reassembled the shards into the most gorgeous cubist, gothic window.

This piece (pointing to As It Happened and Where It Went) was from the first torn pieces that depicted wood grain. And this is the earliest piece in the show. The gap between vinyls is the torn edge of the found material. I featured the gap by translating it into different vocabularies across the panels.

MA: It seems like you use the Fibonacci sequence to arrange elements in some of your work. Did you use it in this one?

SJ: No, this has a different ordering system–one panel shifts and another rotates. The arrangement of the depicted rectangles anticipates or repeats the arrangement of the actual panels. It was a way of thinking about translation.

The square paintings use the Fibonacci sequence. It’s especially clear in the big one (pointing to Chicken Chop Cha) where the 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8 is exactly true on the top. On the bottom I decided to drop the fourth panel because the order was already established, and I hoped we would see the gap and fill it in.

MR: So does the use of the sequence originate at the beginning of the process?

SJ: Yes, it becomes a playing field. A lot of artists use the Fibonacci cycle and it’s usually an idea about an ideal order. But I litter it with the debris of a lived life, throwing Aristotle into the platonic form. Le Corbusier used the sequence in many of the buildings he designed. At first I thought I was making fun of him, but I came to understand that Le Corbusier designed simple buildings–he believed that the lived life is what’s important, not the architect. He made them open to adaptation. His idea was not a machine for preservation but a machine for living.

MA: What’s the function for the viewer? How should the viewer take in that structure?

SJ: If you visit the Acropolis, a mathematician can tell you about all of the geometric principles it’s based on, but most people just know that they are at a damn beautiful place. Viewers don’t need to be told how to look. They/we should just follow our observations and take it from there. I talk about the structure as a way of warming up or controlling the conversation, but maybe it just distracts. The order become something I can easily describe. What is valuable in making the work is engaging the things I can’t readily discuss.

MA: It’s hard to discuss things that are hard to articulate.

SJ: Yes, that’s the challenge of our conversation. How we assemble information is as much the subject of these pieces as are the systems I rely on to get started.

MA: We both work abstractly, and we both also use collage. Why do you incorporate collage in your paintings?

SJ: I remember that painting you made that has contact paper printed with an image of hurricane fencing. How did you find that?

MA: Totally by accident, I had been using wallpaper a little bit, but I was buying it in the hardware store. And then, naturally, you go to the internet, and the number of possibilities are huge and categorized. That paper was listed under “Industrial.” It was so beautiful. I didn’t really think about the image as something that can either draw you in or keep you out. I always go with what it looks like, my response to it, and then later I begin to realize that there are other meanings attached to it. The process is completely intuitive.

SJ: That’s why I like my conversations with you. You have a gut response to what you love and what you don’t. You trust your preferences. One of the problems about teaching is I become so rational about art. I know what I think before I know what I like. I love poetry and dance, because I am still subjective and opinionated about them.

MA: When you put collage elements in a painting it’s a tremendous interruption.

SJ: Yes, it changes the language of the paint mark, It changes the surface and the timing.

MR: Are you trying to add disharmony that you hope you can resolve?

SJ: Yes, that’s what I do.

MR: I want to do that, too. Because my space is very tight and flat. You have much more surface in the collage material than I do. Chicken Chop Cha and Massaging Kale are the two that have the most harmonious solution, as opposed to the two egg pieces. In those, the collage elements create a bigger disruption.

SJ: Right, while they employ different systems, these are also two paintings that just happened. I plot things out and let unanticipated relationships happen. The plot becomes a launching pad for a more open activity.

MA: But this one you worked on for a long time (pointing to Chicken Chop Cha)

SJ: Yes, many stages, much of which I finally covered with the chicken, and then I repainted the rest in response to that image.

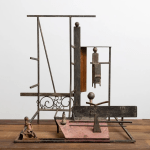

MA: I guess what I’m saying is that it’s the reverse of the egg pieces, in which the objects are added on in a really dramatic way–like the broken rake, breaking out of the picture plane. Does it feel like there�s a contest going on?

SJ: No, I have a few ways to work out similar agendas. What’s important is the fluid relation to the world around me. Some are about the process of making. Others are noisier. The rake interrupts in a different way but it’s still rhyming and rolling with the flat sections.

MA: Is there an overarching thematic content?

SJ: At some point the theme of chicken and eggs became a running gag in the studio, but they are no more important in terms of content than the way the panels are arranged, or how they are painted, or the way the paintings reveal the transitions in the system by which they were made.

MA: Adam (Simon) said that collage provided easy access to content, but I don’t totally agree with that because collage also creates problems.

SJ: It can, but the content is not the subject. It’s easier to talk about the food as spectacle than it is to talk about the way experiences are remembered and repeated, translated and changed, or the way we learn to hold on and let go. I think about the choice to nurture pain or let it go as I attempt to resolve my horror at our political situation with my Buddhist inclinations. The source and implications of my materials are engaging, but they are a McGuffin for the larger consideration of how things change.

“Suzanne Joelson: Slipping Systems,” Studio 10, Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY. Through November 13, 2016.