Contributed by Sharon Butler / Zombie Formalism–innocuous abstraction employing a pastiche of art-historical references and made to fulfill undiscriminating art market demand–has given abstract painting a bad name. Alex Baker offers a vibrant remedy. At Fleischer/Ollman in Philadelphia, where he is gallery director, Baker has curated “New Geometries,” a fine exhibition that showcases geometric abstractionists who take sharp cues from the political roots of Constructivism, Suprematism, and the parallel modernisms of indigenous and non-Western cultures.

In the catalogue essay, Baker sums up the history of abstract painting and then suggests that artists now, unlike those of the Modernist era, are decidedly non-utopian and non-experimental, but fiercely engaged with the real world. “These artists appropriate the history of abstraction while energizing it with new personal, political, and aesthetic narratives. For them, terms like ‘narrative’ and ‘content’ are not antithetical to the concept of abstraction.” The artists he has selected include Martha Clippinger, Gianna Commito, Diena Georgetti, Jeffrey Gibson, Eamon Ore-Giron, and Clare Rojas. The following excerpts, from Baker’s essay, put each artist’s work in context.

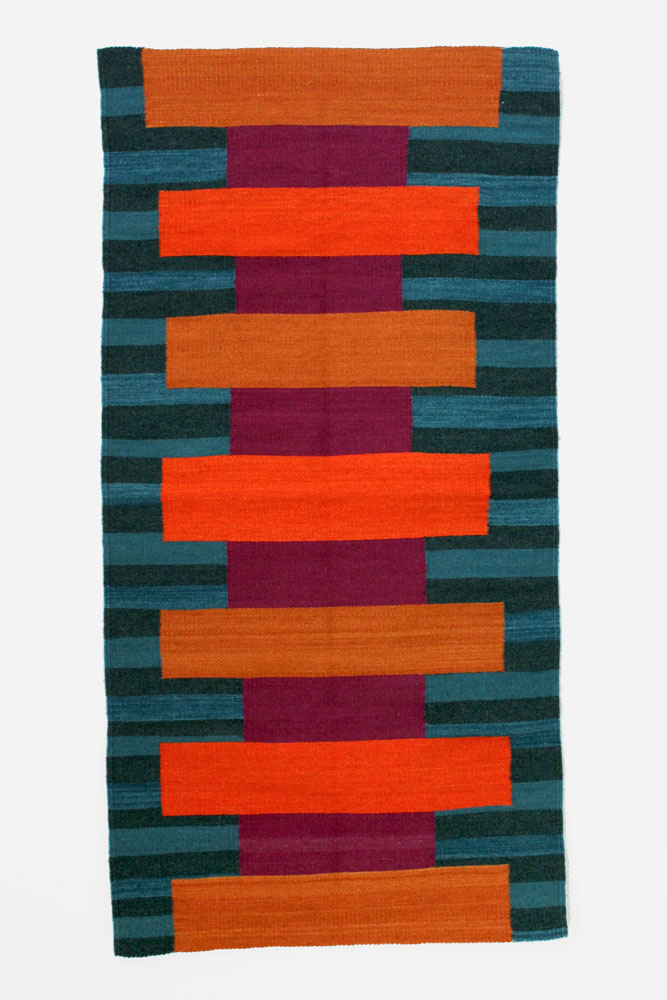

Martha Clippinger�s works included in “New Geometries” are not actually paintings at all, but textiles that evoke aspects of painting (rectilinearity, a relationship to the wall) while also proposing abstraction�s use value. According to the artist, they can just as well be utilized as rugs. Created in collaboration with Oaxacan weavers, Licha Gonzalez Ruiz and Agustin Contreras Lopez, the tapetes (Clippinger prefers the Spanish term for �rugs�) resonate strongly with the history of geometric abstraction, which has found itself in pragmatic contexts including interior, industrial, and graphic design. Textile artists like Annie Albers and Sophie Tauber Arp, for instance, demonstrate that modernism encompassed so-called �craft� just as much as it encompassed �high art� pursuits like painting and architecture. Albers, the artist who put modern textile design in the realm of public consciousness, overcame sexist segregation (as a woman in the Bauhaus, she was only allowed to work in a medium associated with the �feminine�) and made geometric abstraction accessible through the mass marketing of her designs, democratizing modernism perhaps more than any of her male peers.

While Clippinger is an artist of the 21st century for whom the craft-versus-high-art and gender-equals-medium debates seem obsolete, it is difficult not to ruminate on Alber�s debt to geometric abstraction and the gender politics of modernism when looking at Clippinger�s daringly colorful and exuberant tapetes. Clippinger also makes small-scale, painted, wooden constructions with similar geometric patterns and color combinations (not included in the exhibition). Like the tapetes, Clippinger sees these objects as flexible in terms of their display, occupying spaces not usually designated as places for exhibiting art works, including ceiling and floor corners, window ledges, and bookcases.

At first glance, or from a distance, Gianna Commito�s paintings seem perfectly executed. However, careful viewing rewards the viewer with Commito�s layered, fractured, and scaffolded forms, a handbuilt imaginary architecture. Ledge marks, visible underpainting, and paint loss collectively conspire to give Commito�s paintings an imperfect appearance, an intentional affront to the seamless geometry that confronts us when first stepping into the gallery. One may be tempted to situate Commito within a modernist lineage celebrating the machine and the city (think Italian Futurism or American Precisionism). However, Commito is more interested in entropy and folk architecture than paeans to progress.

Taking her cue from both the chaos of urban development, where contemporary and antiquated buildings exist side-by-side, and rural, 19th-century farmhouses composed of weathered clapboard in which additions are appended onto a central house structure evolving over time, Commito�s paintings relate a narrative of change�uneasy unions between colors, forms, and patterns. Commito paints with casein (a milk protein, water-based paint) on marble dust panels which further contributes to the push and pull of polished and weathered, resolved and chaotic, and vibrant and muted.

The three paintings by Diena Georgetti included in “New Geometries” are from her Folk Modern series. The phrase �Folk Modern� suggests a juxtaposition of terms that seem diametrically opposed. However, Georgetti synthesises these supposed opposites by combining the utilitarian and decorative tendencies that underpin the generic conception of the word �folk� with the non-representational and non-functional attributes that we often associate with �modern� by painting geometric abstractions with use value.

Identifying herself as a painter, curator, and collector all at once, Georgetti sees these paintings as having a particular purpose within a domestic setting. Incorporating a range of touchstones in her work, from Frank Stella, to Brazilian Concrete Art, to children�s Naef play blocks, to Bauhaus decorative art, to symbols such as energy arrows, Georgetti believes that the Folk Modern series emanates powers that directly affect viewers: one painting acts as a protector, one as a motivator, and one as a mood enhancer.

Since the late 1990s, Georgetti has been channeling modernism in its myriad forms (from painting and sculpture to interior design and fashion), creating paintings for imaginary, domestic contexts inhabited by phantom aesthetes. Georgetti�s paintings also resonate with the early history of abstraction, in which Spiritualist theories on the metaphysical possibilities of symbolic form could help human beings navigate the unchartered waters of technological progress, urbanism, industrialization, and mechanized warfare�in short, the alienating experience of modernity.6

Both colorful and incorporating materials that may signal domesticity, Jeffrey Gibson�s paintings are also dense with personal and cultural significance, with the specter of modernism always looming nearby. Included here are geometric paintings on army surplus blankets and one on rawhide over an antique ironing board that impart Native American and modern narratives simultaneously.

The blanket has a rich history and present-day significance for Gibson, who is Native American, as blankets have been exchanged as gifts celebrating major life events for multiple generations. From self-created designs, to blankets made specifically by companies like Pendelton for Native American consumers, to the disturbing historical narratives regarding the US government allegedly giving smallpox-infected surplus blankets to Native Americans in the 18th and 19th centuries, the blanket has long been a symbol of cultural identity and exchange. The blanket continues to maintain strong cultural significance for Native Americans to this day despite being designed and marketed by whites to Native peoples and despite the blanket�s association as a symbol of genocide.7

For several years, Gibson has created shaped canvas paintings incorporating rawhide as support material. These works evoke the actual use of hide in a range of Native American aesthetic practices (such as clothing, drums, and shelters) and the history of the shaped canvas in modern and contemporary art. In “New Geometries,” one of Gibson�s shaped canvas paintings uses the armature of an old ironing board multivalent in meaning: a readymade, shaped canvas; an homage to his grandmother who was a meticulous housekeeper; and the transformation of a domestic object into a power object�a shield. Gibson synthesizes form and content by using culturally and personally meaningful materials (blankets, rawhide) as the surfaces for abstract paintings. Here �content-less� abstraction is imbued with meaning not usually associated with geometric abstraction.

Eamon Ore-Giron originally worked in figuration before developing his signature abstract style. His paintings resonate with artists and movements of the past and present, including Suprematism, Latin American Concrete Art, the geometric minimalism of Cuban- American painter, Carmen Herrera, and the modernist-inflected paintings of Mexican contemporary artist Gabriel Orozco.

Ore-Giron uses CDs and dubplates from the music he once made as templates to create structures for his paintings. The bright colors and designs on expanses of raw linen bring to mind Moholy- Nagy�s paintings of the 1920s, which prominently featured similar, unpainted grounds, but these might just as well originate from Ore-Giron�s coming-of-age in Tucson, Arizona�an arid environment in which color always pops in the brown landscape. Recently, Ore-Giron has been integrating gold into his color palette, evoking the great traditions of gold artistry in countries like Peru�his father�s birthplace, and a place Ore-Giron continues to strongly identify with.

Ore-Giron�s paintings also bring to mind the indigenous futurism of the Bolivian architect, Freddy Mamani Sylvestre, whose chromatically intense, space-age buildings reference motifs and colors popular in Aymara culture, as well as sci-fi themes appropriated from Transformer movies. Interestingly, Ore-Giron also shares an indigenous heritage and wonders if there is something in our background that pulls us toward bold, bright colors and stacked circular forms�it could be a cultural approach to color we both share. I love the concept of indigenous futurism because it�s so easy for people to place indigenous people in the idealized past, but in places like Peru and Bolivia where 60% of the population is indigenous, they engage technology just like people in the developed world, they use 808 drum machines to make their music, they do their banking on smart phones.8

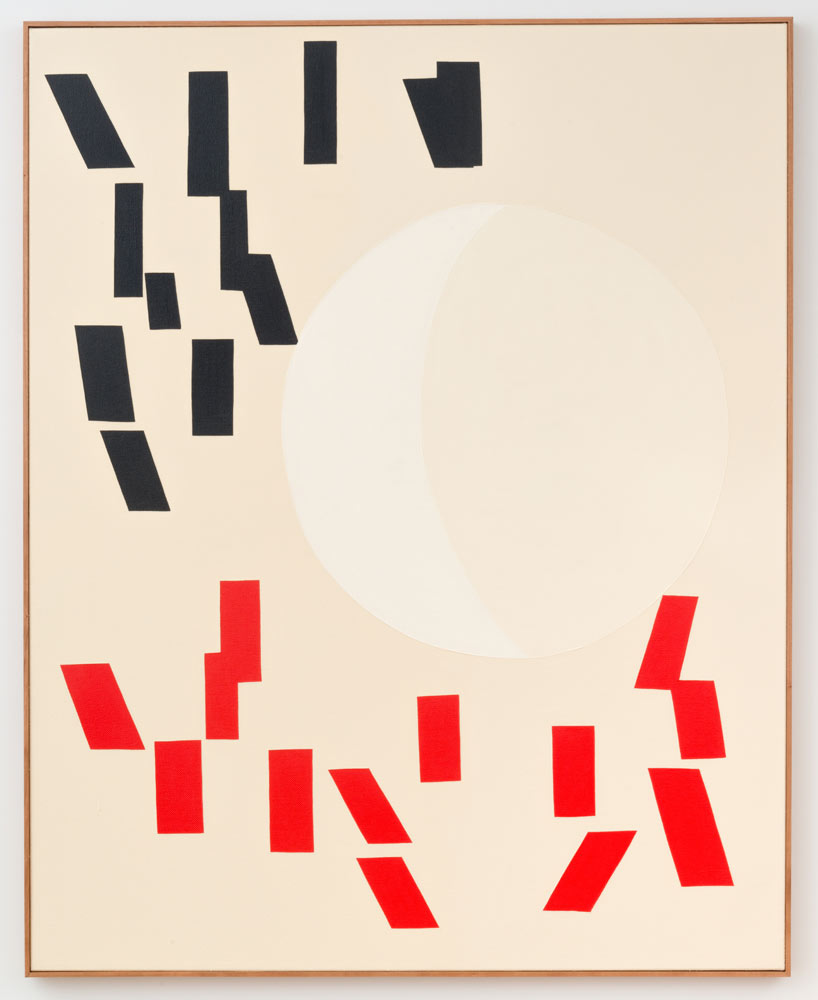

Between 2000 and 2010, Clare Rojas was renowned for her folk art-inspired figurative paintings exploring gender relations. In a radical shift, she began abstract painting in 2011, jettisoning all narrative references. Still, there is a strong relationship between the patterns that served as the settings for figures in her previous work and her recent abstractions. Often painted on stark grounds, her new compositions evoke Malevich�s Suprematist painting, in which sharply delineated shapes float on expansive fields. Echoing Malevich�s notion of faktura�that paintings must present themselves as having been made by the topographic materiality of their surfaces�Rojas leaves visible brushstrokes and traces of her hand in her work. Interestingly, both Malevich and Rojas� earlier work is steeped in an appreciation of folk art.

Malevich painted Russian peasant scenes in a Cubist manner before taking up non-representational painting, and Rojas painted matryoshka-like doll figures alongside hex-sign and Amish quilt-inspired patterns and borders. For the installation of Suprematist paintings in the seminal exhibition “The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10,” Malevich honored the Russian peasant tradition of hanging a Christian icon high up in the corner of a room, by displaying a black, square, monochrome abstraction in this revered location.

As a contemporary artist working in geometric abstraction nearly a century after Malevich, Rojas never takes up Malevich�s firebrand polemics which sought the Truth through abstraction. To do so today would be naive and historically redundant. However, Rojas seems to share with her visionary ancestor a belief that abstraction can be a utopian practice. Before her shift to abstraction, Rojas explored gender politics where women and men uneasily coexisted in vaguely sinister, fairy-tale environments. Feeling that she had painted herself and her female protagonists into a corner, Rojas turned to abstraction to create a refuge. Rationalizing her decision, she relates a Buddhist parable with utopian overtones�perhaps Rojas� more modest, personal variation on Truth in abstraction�in which a woman who is surrounded by vicious tigers stops to eat a delicious strawberry, choosing to savor the present moment instead of worrying about the past or future suffering.9

“New Geometries,” curated by Alex Baker. Fleischer/Ollman, Philadelphia, PA. Through November, 12, 2016. The excerpt above are from the exhibition catalogue.

Notes:

6 For a comprehensive investigation of the Spiritualist and Theosophical underpinning of early abstraction and a cogent argument regarding the idea of content and meaning in abstract painting, see The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890�1985, ed. Maurice Tuchman (Los Angeles/New York: Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Abbeville Press, 1986).

7 For an overview of the commercial trade blanket as a commodity marketed by white industry to Native peoples, see Diane Dittemore and Nancy J. Parezo, �Artifact: Indian Trade Blankets,� Arizona State Museum, There have been controversial theories proposed by historians regarding the intentional spreading of disease to Native Americans through the distribution of infected blankets. See Ward Churchill, Indians are Us?: Culture and Genocide in Native North America (Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press, 1994). For a critique of the genocide-by-way-of-blanket argument, see Guenter Lewy, �Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide?,� September 2004, History News Network.

8 Eamon Ore-Giron, email to the author, June 22, 2016.

9 Gwen Allen, �Clare Rojas: Gallery Paule Anglim,� Artforum (September 2014), p. 383.

Related posts:

Speculating on Andy Boot and Zombie Formalism

Responses to �Zombie Formalism�

Geometric Abstraction update in DC

Hurray

Make it real.

I recall this article from 2015 about the influence of Stella on current abstraction,mostly zombie https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-frank-stella-has-had-a-disproportionate-influence-on-contemporary-art

It is hard to push abstraction into narrative considering over 100 years of pure abstraction. You have to go back to its roots in Mondrian and Kandinsky to find its connection to narrative. But I do think it has to be done unless you want another 100 years of zombieism.I suggest a solution to that problem here http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2015/03/a-report-from-lighting-out-for.html

Paul Pollaro revives Halley as someone setting the stage for this group of artists in this email he sent me:

” And what I’m also trying to say that for a while now painting has focussed on new languages (which we absolutely have to have because it’s the way we evolve) but the focus is on the fact that we have new languages and not what the new languages bring forth. The fore fathers of Post modern/post industrial painting were Halley, Salle, and Bleckner in the late 80’s. Halley represented deconstructing the sign itself. Solid rectangles of color no longer referred to the spiritual but to computer cells and conduits. Bleckner deconstructed the triggers of figuration and romanticism and made figurative painting conceptual. The romantic still life was now about the romantic manipulation of the viewer by the artist.

Salle was the true father of all the shake and bakers. The everything but the kitchen sink approach..the NY minute. The simultaneity of stimulus in a media culture. This is the way most have gone I guess because it’s, for one, the easiest where you can avoid responsibility of decisions and also because of the computer age. BUT, like in the article you send me about ‘bricolage?” sp? The emphasis needs to be in how the new languages add up to new idea and experience not a simple presentation upon presentation of the language itself. That’s where I think a lot of new painting is stuck. Like when i said the idiosyncratic touch of the artist isn’t in a vacuum, it’s in response to figuring something out very idiosyncratic and personal.

What are the employs of the new languages bringing out..bringing forth?

I want to thank you for this inspirational work about the new geometrics. For me it’s a simple pleasure to like and understand this

artwork.

Mindfulness is good. Immediately, I would like to understand custom carpet in the Grecian style.

I like your articles.