Contributed by EJ Hauser / Jennifer Coates paints food–fast food, junk food–anything easy to make and portable. On the occasion of “Carb Load,” her compelling solo exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (her alma mater), we met at PAFA, to discuss painting, food, gratification, entoptic phenomenon, geometric hallucinations, and more.

EJ Hauser: Hello, everyone. Thanks for being here today. This is a real treat for me to have a conversation with Jen Coates, who besides being an awesome painter, is my friend. We met at my studio a few weeks ago and we discussed some ideas related to her work here in the gallery. Before we talk specifically about paintings, I wanted you all to know that Jen’s got a kick-ass article in Modern Painters this June/July. It’s called “The Goo of Paint: How Every Mark Matters.” Jen starts out the essay by mentioning Mira Schor’s seminal essay,“Figure/Ground” which is a feminist painterly battle cry acknowledging the bodily and the goo in any account of art history. I feel like this is a great place to begin.

Jennifer Coates: I read “Figure/Ground” when I was in grad school and it blew my mind because it was a way of re-animating art history. She wanted to acknowledge the malleability, the pliability of this colored gooey material that we use as painters. She wrote it around 1990, right at the height of body art, which was a feminist-oriented art that was about the fragility and liquidity of the body.

I loved that idea of connecting the bodily with the history of paint and looking at the continuum of different ways one can treat paint, from action painting to realism in those terms. In every painting there’s a moment where the materiality of the paint asserts itself and becomes a sort of magical experience where you’re aware of its physicality as well as its role in supporting pictorial content.

EJ: Kind of like a symbol almost.

Jen: Yeah, I wrote in my article, paint is an alchemical shape-shifter. It can be all these different things at once. That’s why I’m seduced by paint.

EJ: Do you think that the realization that you had after reading Mira Schor’s article was something that you were less aware of, like when you were a student here?

Jen: When I was a student here, I went through all of these very traditional classes of still life, landscape and painting from the model and I loved all of that stuff, but I had it in my head that I needed to branch out of painting. I didn’t really understand how pliable and malleable paint could be, that I didn’t need to switch media in order to talk about the fragility of the body. I could use paint to talk about anything that I wanted. The early student work I made was out of paper and textured materials and was really influenced by Kiki Smith — bodies and organs that were bloody and oozing.

EJ: Really gooey.

Jen: Which has a weird conversation with the work that I’m doing now. It’s fun for me to remember what I did twenty years ago, think back on that and how it talks to this work that I’m doing now about processed food.

EJ: Let’s talk about processed food.

Jen: Let’s.

EJ: Let’s talk about junk food. I think one of the things that I really dig about your paintings is all of the layers of how the paint is communicating to us, not just about these gooey bodily things, but the narrative of junk food that we talked a lot about. Do you want to tell me some of your ideas?

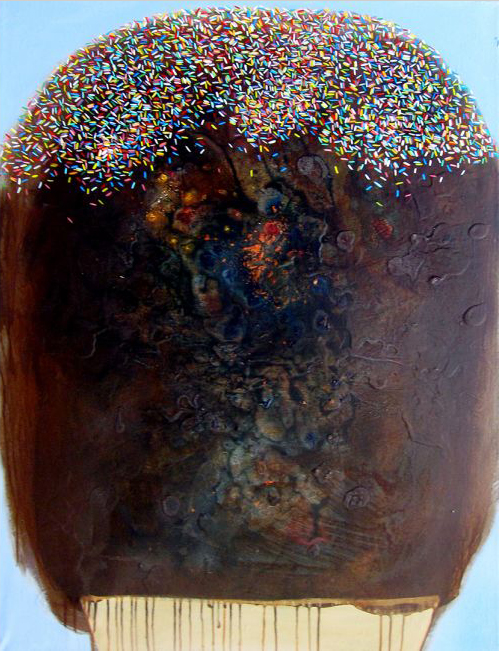

Jen: The way I see processed food, it’s on the one hand a guilty pleasure. It’s this thing you want to turn to for comfort. It’s often pre-packaged or ready take away, it’s easy to carry around with you, you can just grab it and it gives you this instant gratification, but maybe later on you get a stomach ache, you feel not so happy with yourself. I’m thinking about those things when I’m painting processed food, but I’m also thinking about what is the deep history behind these items that we might take for granted in our day to day life? The ubiquitous ice cream cone or danish or sandwich to go.

I started researching and thinking about where these forms came from. Where do the colors, the synthetic dyes come from? Where do their structural logics come from? For instance, I’ve got paintings of a blueberry danish and a cinnamon roll and they’re both spiral-shaped. If you look into the history of the spiral, it’s got this really deep interesting iconic history in different cultures. It goes back to Neolithic sculpture and Paleolithic caves. There’s a passage tomb in Ireland, Newgrange, that has these beautiful stone-carved spirals on the outside. I started thinking, maybe these day to day items could be portals back in time and a way to kind of connect with more primitive building impulses and shape attractions.

EJ: Right. Something that Jen explained to me is entoptic phenomenon. Entoptic phenomenon, and stop me if I get this wrong because I’m a bit of a newbie on this, but have you ever seen patterns or clouds of light, when you close your eyes, or floating colored shapes inside your eyelids? If you touch the outside of your eyes lids you’ll see that something happens in your field of vision. What happens is an entoptic phenomenon. It’s a kind of disruption in the visual cortex. Your eyes are trying to put back together what is going on in the visual cortex, and the result are these kinds of patterns, sometimes almost glyph-like shapes.

Jen: Entoptic means it originates in the eye or in the visual cortex of your brain. Sensory deprivation can cause these kind of geometric hallucinations, as can certain psychedelic drugs, or starvation — among other things. Entoptic phenomena are very specific types of shapes and patterns: lattices and grids, concentric circles, spirals, zig-zag lines, wavy parallel lines. It’s been documented that there are categories of forms that people see. There was this German scientist in the 1920s, Heinrich Kluver that did experiments with people, giving them mescalin and seeing what kinds of drawings they made when they were under the influence. They are known as Kluver form constants and they are the same as the forms that are found in Paleolithic rock and cave art. There’s a theory about this kind of art. We’re all familiar with the animals in the French caves, but there’s a huge amount of visual information there that is non-objective and no one can know what it means, but a lot of these shapes conform to the different categories of entoptic phenomenon. There’s a really interesting book called The Mind in the Cave by David Lewis-Williams, an archaeologist. He has this theory that there was shamanic use of plant hallucinogens in Paleolithic cultures and so they would descend into the caves and have rituals and draw these abstract forms. I love this idea.

EJ: Almost like they were tracing on the wall what they were seeing.

Jen: Yeah, exactly. Translating their geometric hallucination, sometimes superimposing them on the animals that are more realistic, like two types of seeing at once. I like to think that all the banal things that we surround ourselves with – processed food, bathroom tile, plaid shirts – have a magical, ritualistic purpose underwriting their structures. There are patterns and shapes that occur at different time periods, in different contexts all around the world. It’s Lewis-Williams’ theory that the reason why they do is because we’re all embodied in the same neuro-anatomy and when you have these hallucinations it’s your eye looking back on your brain and seeing how your brain works. It was very exciting to me, really. It doesn’t have to be true, but it’s working for me.

EJ: One of the things that I like about your practice is you really use it as this way to pull in so many of the things that you’re interested in and tell that story. One of the stories that I think you’re telling is evidenced by your curation and arrangement of the paintings inside this gallery. They are hung in groupings and I feel like they are arranged not unlike the stations of the cross inside churches or cathedrals.

Jen: I looked at this beautiful, weird space as an opportunity to capitalize on its chapel quality. There are these architectural details and it’s this amazing old building, there’s even a little niche back there. I just thought, let me just use this particular context as a chance to make almost a religious setting. Here are these devotional paintings of processed food in iconic, almost anti-compositions. Singular shapes hovering in the middle, hopefully with some kind of central force to draw you in, whether it’s color or texture or light. I just thought it would be really great to see this as a devotional shrine to processed foods. We’ve got the circular snack nook of three paintings in the niche and the three breads along the main wall.

EJ: Do you want to talk a little bit about your ideas about peanut butter and jelly and sandwiches?

JC: Sure. I have all these theories. Every time I paint a food item I think, where did this come from? I try to substantiate it when I hit on something that seems plausible, but it’s just fun to create a narrative behind whatever it is I’m doing. When you’ve got your blank piece of bread and you’ve got your knife and you’re digging out the peanut butter and jelly and you’re putting it on the bread, everyone uses different ratios of peanut butter to jelly. Is the peanut butter going to meet the edge of the bread? There are a lot of aesthetic decisions.

In certain food preparation moments, it’s almost like painting asserting itself into humanity and saying – you know you want to be a painter. You know you love doling out the peanut butter and jelly. The bread is a stand-in for the canvas. But behind that, it’s kind of violent. You’ve got this knife, right? I was just thinking what is the initial early version of taking a knife and spreading some gooey bodily-looking fluids on an empty slab. What about sacrificial altars? You’ve got this bounded space of the stone slab. Someone is killing a person or an animal with a knife and the innards go spraying about in this bounded area. Maybe the sacrificial altar is the first abstract expressionist painting. That’s my theory.

EJ: Peanut butter and jelly will never be the same. It’s interesting, this is making me think about other paintings in art history that include food, all the dead things in these still life paintings, they’re so bloody and violent.

Jen: It was supposed to be about the transience of life, right? The vanitas subject matter.

EJ: Right. Do you feel any of that in your work?

Jen: Definitely, there’s decay everywhere. As much as I’m celebrating something nostalgic and joyful, like ice cream with sprinkles, happy rainbow colors, there’s also rot happening and that’s really important to me – to invoke the two things at once.

EJ: That seems to really come back to your point about goo and paint. You look at the surface of your pieces and it’s not just an illusion of food. It’s also the palpable goo of the paint which is something I think is really fantastic about these pieces.

Jen: I want there to be moments where the materiality of paint pushes up on the surface and is maybe even distasteful. Paint is just a very magical thing – how it can be material and present and thick and gooey but also be atmospheric. Like Turner landscapes, you have these skies that are super encrusted and thick that are often the most ethereal moments in the painting, really. All of the boats and the figures are very incidental and you’re caught in this tidal wave of gooey encrusted paint and yet this solid matter can transcend itself and become light at the same time. I think that’s just amazing and cool.

EJ: Another thing that strikes me about food is that a lot of times it’s women who are the preparers of food and we talked a lot about how processed food has an aim at women specifically, when it appears in the culture after World War II. And you connect this to processed foods’ portability.

Jen: There used to be something called portable rock art in the Paleolithic period. People would walk around with the little venuses, carved animals and figurines and they were meant fit in your hand or be put on a necklace. I thought about processed food in the same way. You go to the store and get something to carry away with you, there is maybe an ancient comfort in that beyond just satisfying hunger. I’m always looking for what the predecessor behaviors are for the things that we do that we think are so modern. We think that we’re so separate from our prehistoric selves but anatomically we are the same. We’ve been the same for, what, a hundred thousand years I think? Whatever I’m looking at or thinking about, what’s the origin? The portal back in time.

EJ: Exactly. I wanted to go back to the entoptic for a minute, is there a particular culture that you’ve looked at that uses that kind of entoptic imagery that you were looking at when you were creating this body of work?

Jen: David Lewis-Williams’ suggestion is that it was happening all over the world, it didn’t matter what culture or what time period or what race, it’s more universal. I’m attracted to these generalizing narratives that tie everything together, which can be, I’m aware, kind of problematic sometimes, but it’s just how my brain likes to work. There are instances of it in South African cave art, in French and Spanish caves, Aboriginal art, Native American petroglyphs. I think it’s more that I’m looking for where the same shapes pop up rather than at one particular culture.

EJ: I was trying to lead you someplace, but I’ll just go there, which is we were talking about the Shipibo embroidered pieces. The Shipibo culture is in Peru in South America and the reason why I’m thinking about them is that their work combines not just a literal map of how to get someplace, but it’s also a way of storytelling and it’s music all layered on top of each other. And there are so many examples of this in cultures where these kinds of entoptic patterns are in use.

Jen: You have an image or a pattern and it’s never just decorative. That assessment really bothers me. It’s never just utilitarian. When you go further back into ancient cultures or even current indigenous cultures, images and patterns were meant to represent many things at one time and I love that. I think we have the ability to reinvest the things that we think are meaningless around us with meaning. Maybe a s’more is not going to make music for you, but you could find something outside the s’more that points to consciousness in some convoluted way.

EJ: What’s after junk food, Jen? Is it kale? Quinoa? Food is just so loaded. Even if it’s good for you … I love quinoa, speaking of quinoa, and then somebody recently told me that quinoa is also problematic.

Jen: Yeah. Our first-world obsession with it has made it bad.

EJ: It’s made it unaffordable in the place where quinoa is actually grown. The politics of food —

Jen: That’s something I think about a lot – all the choices we have and all of the processing and production that go into these choices. Processed food is really problematic for the environment. I enter a supermarket or a drug store and I just think “It’s too much choice.” We know at this point that there’s something wrong with the fact that we can have whatever want whenever we want it and there are huge parts of the world where people are starving and have no electricity.

EJ: And we throw so much away.

Jen: Right, we throw it away, we go to restaurants and they clear our leftover food into the garbage and we don’t think twice about it. For me, you can’t put an ice cream cone or french fries or a piece of bread up on a pedestal like this and not say, “Really? Is it really just about being delicious?” I think the paintings play with desire and a nostalgic longing – for a time before we had to worry about what the planetary consequence was for consuming so much- but I want to somehow interrogate the food with an awareness that it’s problematic at this point.

EJ: It’s being pitched to us in this really intense way and we’re supposed to desire these foods, right? When I walked into the gallery the night of your opening, there’s this thing like, “Oh, fries, oh, danishes.” Everything you kind of want/don’t want is on the wall. I had this similar experience … Jen has probably what, Seventy-five, eighty paintings that are all based on junk food and I visited her studio and it’s like a little overwhelmingall — the wrong food choices. How did you deal with that in the duration of making these paintings?

Jen: It’s funny because when people came to my studio when I had them all installed on the wall, it was sometimes an overwhelming experience. For me, I’m used to it and it kind of works with my brain. I can live with it but some people would come in and say, “I can’t even see anything. There’s just too much.” Originally I did all these small pieces thinking that they could be an installation in a small gallery space and it was going to be a salon-style hang, floor to ceiling. I would call it “Total Fat” and my husband had this idea that the checklist could be laminated like a menu.

EJ: That was maybe a little greasy?

Jen: Yes! Oh, I have something else I want to talk about!

EJ: Let’s talk about it!

Jen: Ok. Another thing I’m trying to deal with in my work is the history of painting. Taking abstract expressionist moves, for example, like the icing on the blueberry Danish – that’s my chance to be Jackson Pollock for a minute. The breads with jam are like Mark Rothko color fields within the confines of the bread. The one called “White on White” which is a little joke on Malevich’s painting of a white square on white. I’m trying to have fun with art history. I think about the checks on that checkered tablecloth on the sandwich painting are sort of like Renaissance floor pattern —

EJ: And maybe Bridget Riley?

Jen: Yes that too! I say this in my article about Jason Stopa, but it’s true for me too – that I try to view art history not like this cemetery filled with dead people, but a supermarket when you can go and just pick this and pick that and take whatever you want and kind of put it together in the right ratio. Somehow the food subject for me really opened up my relationship to paint. It made it possible for me to paint in whatever way I felt like according to my mood. Sometimes I need to work with that little brush and sometimes I have to make a big spill and a huge mess.

EJ: Since we’re sitting here at PAFA, I’m going to ask you do you paint from observation?

Jen: I do not. I did at one time and I do not now but I do a lot of image research. I never paint from photographs, but I love to Google search and I also just stay alert walking down the street — I love food trucks – there are all these appetizing photos of food.

I’m always looking at images of food, mostly food stylist images. I prefer an aerial view or a cross section because of the straightforwardness, the dumbness of it. When you look down on a casserole dish, it’s like the casserole dish is the canvas and the sauce is the paint. It just makes it very clear to me that there’s this funny one to one relationship with food and paint. I’m just trying to find images that push me in that direction, but I’m too undisciplined to paint from real life or from a photograph. That’s the abstract painter in me.

EJ: Right. It would also be very problematic to have lots of junk food around.

Jen: It would be. It would also smell kind of weird and it might attract rats.

“Jennifer Coates: Carb Load,” Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA. Through July 17, 2016.

Related posts:

Food and beverage art: Coates, FOODshed, Honeycutt, Beavers, and more

The Swerve: When gone-wrong goes right

——

Two Coats of Paint is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To use content beyond the scope of this license, permission is required.