“Painting is a medium in which the mind can actualize itself; it is a medium of thought. Thus painting, like music, tends to become its own content.” � Robert Motherwell

Guest contributor Laurie Fendrich / During the two and a half decades I was a full-time painting professor before retiring in 2014, followed by the year and a half I spent as a visiting artist at two prominent art schools, I observed dramatic shifts in ideas about teaching painting. Professors of my ilk see painting as a hands-on art form best learned through looking at great paintings and at painters in action, and by painting while being coached. The new pedagogy has been endorsed mostly by younger painting professors but a few geezers too, who see painting as best learned through critical thinking, a method borrowed from literature and the social sciences.

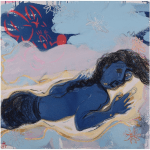

[Image at top: Laurie Fendrich, Loose Talk, 2014, oil on canvas, 38 x 36 inches.]

�Skillfully analyzing, assessing, and reconstructing� a subject, �critical thinking is self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking.� So says the Critical Thinking Community. The approach benefits disciplines based in words, and I use it myself when teaching modern art history and humanities seminars. But it�s a disaster when used to teach painting, whether to college art majors who want to become painters, to students who want to go into neighboring fields like graphic design or photography, or to biology students who decide to give painting a try.

Applied to painting, critical thinking too often ends up calling into question the very medium�a deconstructionist impulse that particularly sabotages beginning students. Playing baseball or tennis requires accepting the game as a whole, and so does painting. But unlike baseball or tennis, painting is an open-ended pursuit without any numerical victory or defeat. It�s fraught with subjectivity and uncertainty. It is, as an artist I know has said, one semi-mistaken brushstroke after another applied until a kind of truce against the possibility of a perfect painting is reached.

Painting is particularly ill-suited to the critical thinking that has become ubiquitous on college syllabi and de facto mandated by outcomes-assessment mavens who demand that all professors, even art professors, articulate �desired outcomes� from specific �goals and objectives.� Nonetheless, given the corporatization, bureaucratization, quantification, and discrediting of subjectivity and taste in higher education, it has been able to establish first a foothold, then a beachhead, and ultimately a colony in that most unlikely of places, the college painting classroom.

By sidestepping its subject, critical thinking inadvertently bolsters the old idea, around since Plato but not in full flower until the Romantic era starting in the 18th century, that art can�t be taught. In a cloudy, anti-pedagogical way, it�s true: The spark of inspiration and creativity involved in making art is mostly beyond the reach of teachable knowledge, unless you give credence to those airport-bookstore self-help books and online you-can-be-an-artist boondoggles. Equally true, however, is that this idea has had an insidious effect on art students and professors because � on the ground, as they say � it�s an invitation for professors to stop teaching and students to stop learning.

With today�s identity-conscious students wanting, right off the bat, to express in paint ideas about anything from gender crossing to wealth inequality to global political oppression, competence in painting�s traditional skills has become almost a no-go zone. Painting professors have retreated to merely �supporting� and �nurturing� student painters, asking only that students �articulate� what they�re trying to do � that is, to retroactively apply critical thinking to their works. As a result, a lot of students leave painting courses prematurely feeling good about themselves because they�re able to talk some pretty good contemporary smack about art. But few have learned much about painting.

In the fall, I had some extended conversations with the renowned California painter Wayne Thiebaud. A professor of painting at the University of California at Davis for almost 40 years, and after that perhaps the world�s most famous art adjunct faculty member for another 16, Thiebaud is a spry 95-year-old who spends most days in his studio and plays a lunchtime hour of tennis every day. He rose to national prominence in the early 1960s with his thick, cheery paintings of lusciously colored candies, pastries, and cakes. For a while, he was considered one of the original Pop artists, along with Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Claes Oldenberg. He moved on, however, to paintings of exaggeratedly steep San Francisco streets, landscapes of the flat midriff of California (where, save for a brief stint in New York, he�s lived most of his life), and lonely human figures.

Thiebaud has the kind of talent and bravura that lets him teach by painting his assignments as continuing demonstration, alongside his students. In that, he�s a rarity.

�Painters don�t really want to paint in front of anyone,� he says. �They prefer to make their mistakes without anyone watching. But this is a great way to show students how the act of painting is done by a living painter � as opposed to Titian, who isn�t here.� From his friend, the abstract expressionist painter Willem de Kooning, Thiebaud learned that painting is �a process of starting over at every stage.� Painting offers, in other words, constant and multiple paths to success (and failure). Thiebaud�s love of tennis might come from a similar virtue: The game (like baseball, but unlike football) promises a chance of victory right up to the very end.

Thiebaud believes the two most important things a painting instructor must teach are how to render a three-dimensional object convincingly on a flat surface and how the painter�s combinations of color create the sense of light. Practice-centered teachers like me, though we vary widely in our methods, essentially agree. We introduce students to painting through fundamentals � basic color theory, the behavior of pigment color, principles of composition, ways to make paintings appear flat versus ways to create three-dimensional illusions, paint handling, a little chemistry, and a few art-historical examples of artists (�douard Manet, George Bellows, Alice Neel, Helen Frankenthaler) who handled paint particularly well. As Thiebaud puts it: �To call everything art is an obfuscation for the students and fails to clarify what we�re trying to get at as painters. Painting is concrete, but art is abstract. I don�t think we know what art is. But we know a lot about painting.�

So how did critical thinking get into the mix? First, there are many administrators who like the way it makes otherwise incomprehensible images appear rational. Then there are painting professors who embrace it because they think it gets rid of stodgy, laborious, and boring foundation requirements that crush the souls of young, sensitive students wanting to express themselves. There are also those who think that 150 years of modern art obviate both the need for, and the possibility of, teaching fundamentals. What kind of �fundamentals� did Marcel Duchamp or Jean Dubuffet or Donald Judd or Joseph Beuys or David Hammons need? they ask. Others note that since the common list of painters who mastered the fundamentals are derived mostly from a pool of white, European males, requiring painting students to attain a certain competence in them is sexist and racist. Finally, much of the hard painting work that rests on the triad of mind, hand, and paint can be, some au courant professors assume, outsourced to photo-transfer, digital scanning, and ink-jet printing. Since techniques are presumed to be instantly available off the technological shelf, a motto of convenience has taken hold in some art programs: �No technique before need� is the buzz phrase � an attitude that strikes me as a lot like saying there�s no need to learn French until you get to Paris.

Meanwhile, some painting professors enjoy the collapse of any shared convictions that painting has universal or core knowledge. After all, that relieves them of the unpleasant task of making judgments about the quality of student work. Once critical thinking takes over, the focus shifts from visible virtues and flaws in the painting in front of everyone to the student�s putative ideas and noble intentions regarding art and what it can do for the world.

Colleges and art schools have traditionally welcomed students in all majors to sample painting for a semester or so, which is OK as far as it goes. Being a painting professor does carry an obligation not only to mentor art majors but to serve a variety of students taking breadth electives. But for those painting students with a feel for paint and a drive to learn, teaching painting through the lens of critical thinking amounts to lost time. I�ve had a depressing number of students in advanced painting classes tell me that when they look back at their beginning classes suffused in thinking critically about the practice of painting itself, they feel cheated because no one required them to learn anything fundamental about the craft itself. They were asked from the get-go � to use the language of art-school catalogs � to ask bold questions, conduct rigorous social and political investigations, and engage in playful creativity.

Even on the graduate level (I do occasional critiques as a visitor), some poorly trained students lack a basic understanding of how pigment behaves, differently from what color theory predicts. For example, in theory, black added to yellow tamps down the intensity and darkens it, but to the human eye, it produces what appears to be green. They don�t know that oil colors appear darker when applied to the canvas than they appear on the flat palette. They don�t understand the subtle and crucial difference between a color�s intensity � its brightness � and its hue or value. Worse, many painting students at all levels don�t care about these things. They�re willing to accept the sourest, muddiest, most clumsily executed painting if an iconography of personal identity or social critique is crudely visible.

Because critical thinking often overlaps with vague ideas about critical theory, critical thinking applied to painting also leads to a lot of rhetorical gobbledygook about painting and the way it conveys meaning. Nowhere is this more evident than in the many student artist�s statements (de rigueur in an age of outcomes assessment) I�ve read over the past several years. Most of them are poignantly well-intended but poorly written. Unfortunately, in the face of demands that they be �articulate� about painting � a part of culture that defies totalization in words � lucidity is lost. In trying to puff up their statements into the jargony prose their professors (particularly on thesis committees) will approve, they pepper them with semi-understood terms lifted from postmodern literary theory.

It�s not uncommon for painting professors � few of them trained in Continental philosophy, or any other philosophy, for that matter � to bandy about such words as �identity,� �oppression,� �pictorial discursiveness,� and �ontology.� Gone is the idea that painting is understood only by groping one�s way to imperfect meaning through poetic expressions or universally understood metaphysical ideas. The imaginative writing of, say, the poet and art critic Frank O�Hara or the aesthetics-focused philosophizing of the painter and scholar Robert Motherwell would be nearly incomprehensible to today�s painting students, many of whom have grown used to hearing painting talked about as if it were the subject of a sociology dissertation.

The art world sets an unfortunate standard in this unreadable stuff. For example, here�s an excerpt from the Museum of Modern Art�s press release about its 2015 �Forever Now� exhibition of contemporary abstract painting:

The artists in this exhibition � use the painted surface as a platform, map, or metaphoric screen on which genres intermingle, morph, and collide. Their work represents traditional painting, in the sense that each artist engages painting�s traditions, testing and ultimately reshaping historical strategies like appropriation and bricolage and reframing more metaphysical, high-stakes questions surrounding notions of originality, subjectivity, and spiritual transcendence.

In other words, paintings as everything but painting.

Painting contains its own roughly defined rules. The art is flat, rectilinear, and smeared with colored pigments. It differs from the many boundaryless arts born in the late 60s and 70s � installation, conceptual, and performance art � where the creators essentially do what they want. A painter can bend painting�s rules only so far before a painting is no longer a painting. Moreover, unlike new genres that only now are building their histories, every painting exists in the long shadow of great paintings from the past.

James Elkins is a professor of art history, theory and criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a lively, prolific writer with first-hand knowledge about painting. He has an MFA in painting to go along with his Ph.D. in art history, and explores painting education in his books Why Art Cannot Be Taught: A Handbook for Art Students (University of Illinois Press, 2001) and Art Critiques: A Guide (New Academia Publishing, 2012). I asked him if painting, bounded and defined by its own rules, might be exempt from the Romantic idea that art can�t be taught.

�Probably not,� he said.

In an earlier book, What Painting Is (Routledge: 1999), Elkins describes in detail the particular kind of uncertainty endemic to painting, beginning with the nonrational ways in which painters throughout history have come up with bizarre concoctions out of such things as blood, urine, and horse hooves to make their paints. While modern chemists have developed synthetic substitutes for most traditional natural pigments, in terms of its gooey, messy essence paint hasn�t changed one iota. Elkins makes the case that painters and alchemists alike handle their materials �without knowledge of their properties, by blind experiment,� and mix their substances not by formula, but by feel.

Yet relying on feel isn�t quite the chancy process it might at first seem. Feel is a way for painters to escape clich�d Martha Stewart colors and discover situational new ones among the millions the human eye can perceive. Because modern painting relies so much on the individual artist�s feel, Elkins doesn�t see much place for concrete knowledge of the Thiebaud-esque sort. �It�s no longer clear that painting is something that requires a body of knowledge that can be studied and learned,� he says. �It may be �stepless� � beyond the reach of any routine education.�

According to Elkins, the prescribed �way to make a painting� was abandoned with the Impressionists, and painters became perpetually at risk of �sliding into a wasteland of mottled smudges with no rhyme or reason.� He doesn�t consider this a bad thing. He thinks painting is a perfect match for our �anxious age� and is �the greatest art form for expressing our place between rule and rulelessness.�

That�s all well and good at the top, with paintings created by good, near-great, and great artists. At that level, yes, the celebrated uncertainty of painting, the way every brush stroke tries and partly fails to correct another, may be impossible to teach, only accessible to the talented through observation and experience. But that approach, in my view, obscures the aspects of painting that are certain and that can be taught.

As painting professors become increasingly enamored of critical thinking, or pressured by academic fashion to embrace it, they lose the ability to understand these aspects, and they abandon pursuing the fruits of direct observation in favor of the dubious pleasures of verbal abstraction. Inspired (if that�s the word) by such flaccidly overreaching exhibitions as �Forever Now,� their students come to the fore as the next crop of �emerging artists� who prematurely indulge in deep social and political readings of their own paintings. Professors aren�t being tripped up by the operational uncertainty of painting � that has always been the medium�s magic and its glory as well as its challenge. What�s hindering them is the faux-uncertainty of borrowed critical thinking that stuffs painting into a box of pretentious words.

Well, then, if the craft of painting is hard if not impossible to teach, and if the theory of painting doesn�t help make great or even good painters, then maybe painting doesn�t fit in the modern university at all, you might argue. What good in an academe increasingly dominated by STEM fields and metrics are painting�s subjective, haptic procedures and its holistic approach?

Lots of good. For starters, its vast range of colors � compare it to the limited range offered by the additive colors of the computer screen�s pixels � and its felt composition within a rectangle offer models for understanding alternative ways to organize what happens on computer screens and smartphones.

More important, with its openness to incorporating chance and accident, and its continual internal morphing as it grows, painting offers a direct demonstration of how innovation can come from within a physically prosaic and limited enterprise. Painting professors and students should abandon the windbaggery of academic critical thinking and remember that, while there may not be any bedrock fundamentals in art, there are plenty of fundamentals in painting. And if now and then they take time to notice when it is stirring, beautiful, and exhilarating � well, no harm done.

Laurie Fendrich is a painter, writer, and professor emerita of fine arts at Hofstra University. She is working on a series of paintings for a fall 2016 solo show at Louis Stern Fine Arts in Los Angeles.

NOTE: This is an edited version of an essay that originally appeared in The Chronicle Review in the March 20, 2016, issue of The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Related posts:

Laurie Fendrich: Why do painters have to justify being painters?

Must read: James Elkins deciphers the Art Critique

——

Two Coats of Paint is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To use content beyond the scope of this license, permission is required.

This is an excellent article and should be read by any artist caught between the obscure gobbledegook and the painted surface.

Painting is essentially a visual experience not a verbal one and I'm always suspicious of esoteric meanings being applied to it.

I believe this article has mistaken "critical thinking" for "critical theory." Painting is a nuanced form of critical thinking. Rendering a form three dimensionally and painting light is a form of thinking, albeit one that is married to the refinement of motor skills. Critical thinking is crucial to the acquisition of these skills, assuming that students are prompted to reflect upon their own habits of attention and other metacognitive capacities as they advance. Evaluating, decision-making, problem-solving, analyzing, even reasoning are absolutely the stuff of painting, although they are not the entirety of it (add desiring, fantasizing….)

Meanwhile, critical theory is a school of thought born out of a particular time period that emphasizes critiquing society via specific disciplines in the humanities (politics, economics, sociology, and literature). Ideas from the thinkers associated with this school of thought are often quite opaque and misused. But that is another story.

Instruction in how to think critically is at the core of how I teach my students to paint and ultimately to learn. As for the other behaviors, I have no idea how to teach a student to be a desiring subject or to find pleasure in the makings of their own mind. But, I can model these behaviors, and I do so. Teaching painting necessitates both.

For the record, I teach oil painting from observation at the college level. I also teach critical theory. (But not in the same course).

To Amy Beecher: In practice, critical thinking is deeply connected to critical theory: As i wrote in my essay, "Because critical thinking often overlaps with vague ideas about critical theory, critical thinking applied to painting also leads to a lot of rhetorical gobbledygook about painting and the way it conveys meaning."

For more on the connection between critical theory and critical thinking, see:

https://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2011/09/20/critical-theory-useful-distinction-or-unconscious-smugness/

Laurie Fendrich

Great article! Ideally students would be versed in critical thinking before they ever reached the college level. But as someone who taught university painting for nearly two decades and who has spent the last 30 years as a serious artist, I know that overthinking a painting can be its death. Talking about painting is completely different from making a painting. But it's very difficult to bring this philosophy to a class where syllabi, learning outcomes, grades, and adequate enrollment (meaning that everything is specific and quantifiable) can become the primary preoccupation of students and professors alike. It was time for me to leave teaching when I began to feel that studio art had no place in the contemporary, corporate classroom. This saddens me because as an art student I benefited from the generosity of teachers who, because they did not suffer the constraints of the requirements of today's classrooms, were able to teach creatively and intuitively, tailoring their feedback to the needs of individual students without regard to generalized and prescribed outcomes. Bless them – they saw their students as individuals who had the potential to offer or "say" something unique to the world.

Ok the dude needs to read Rosalind Krauss(Originally a disciple of the formalist Clement Greenberg, Krauss later became enthralled with newer artistic movements that she believed required a different theoretical approach, which focused less on the aesthetic purity of an art form (prevalent in Greenberg's criticism), and more on aesthetics that captured a theme or historical and/or cultural issue. Krauss still teaches Art History at Columbia University in New York. – See more at: http://www.theartstory.org/critic-krauss-rosalind.htm…)

When I took my teacher training, i was told that the way artists taught each other for 800 years was the best way: do something then talk about it. Critique is what were you going for, how close did you get and how do we get you closer. It's about the student's interests not the instructor's ultimately.

At ACAD I saw a lot of abuse of students for following their aesthetic interests that were either formalist or theorist, causing needless very real pain.

To say one approach is better than another, in a creative endeavor, is incredibly stupid and conservative.

To see the consequences of an unchanging aesthetic purity one need only look at the Egyptian art that didn't change for 3000 years.

The formalists who complain about change are losing sales and grant money and knocking the competition, pure and simple.

I just saw the Jack Bush show at the Esker. Boring rubber stamp art, compared to what contemporary art has to offer with new media and technologies.

Yes, people need to learn to paint draw printmake from observation to train the eye to line shape tone colour texture surface, and then head into the computer lab with that education, and learn that relevant technology as well, then because they are artists, do whatever the fuck they want with it, as artists do.

The formalists I know are mostly marketing a product they manufactured to rich people to not offend anyone. Boring conservative crap. I don't see a lot of creativity or innovation there. next!

a final thought since the light just went on. when greenburg was in edmonton he made them famous by saying that they are 'the real thing' abstract artists. this refers to the spiritual basis of abstraction, kandinsky and the boys. this elevated greenburg to the level of spiritual guide one of the few shamans who can see the truth behind the pigments, this glowing light.

In other words, abstraction is a cult, with all the attendant abuse.

https://www.amazon.ca/gp/product/B001RNPD9M/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?ie=UTF8&btkr=1

Mr. Blackstock needs to a) read more carefully; Ms. Fendrich is not a "dude"; b) learn to spell prominent and relevant people's names correctly, e.g., Clement Greenberg; and most of all, c) not fly off the handle about something with which he apparently agrees. (Ms. Fendrich's essay is about teaching painting in painting classes to undergraduates, primarily beginning painting students; Mr. Blackstock says, "Yes, people need to learn to paint draw printmake[sic] from observation to train the eye to line shape tone colour texture surface…")

One is sorry that Mr. Blackstock apparently matriculated at a school where students were abused and caused "real pain." This has more to do with the teaching personalities of the instructors than teaching undergraduate beginning painters some fundamentals about color, composition, paint-handling, pigments, etc.

The rest of his wide-ranging rant–from ancient Egyptian art to "boring" Jack Bush to new media and technologies–is only borderline coherent, if that.

The mistake made by the deans who set curriculum in art schools is their compulsion to respond to a perceived market place of ideas at the expense of "tried and true" classes that are based on perception for fear they will lose applicants or students will drop out. I personally saw the writing on the wall, as it were, when my class on color perception as applied to painting which was very popular was scheduled against a class on gender theory.There is a place for both but the dean of students setting the curriculum was intent on sending me a message that the times had changed and I had better adapt. I think another problem is that the 20th c engagement with abstraction has not been worked out pedagogically. I addressed the issues here.http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2012/01/humpty-dumpty-effectonce-veneer-of.html

In any case I am glad that Ms.Fendrich has brought up the issue.

Thank you Ms Fendrich for addressing this topic.It is more critical than many artists may think.I saw the writing on the wall as it were when the dean of students decided to schedule a class on gender theory opposite my very popular class in painting from perceptual theory.Although I can accept the place of gender issues in any course of study,the scheduling was a calculated attempt to tell me to catch up with the times. The message was either/or not both. Since perception and color inform much of 20th painting, I think that it's relationship to painting should be part of any art curriculum. Pedagogically I believe most art curricula deal well with value oriented drawing and whatever is current in the art scene but somehow the underpinnings of abstraction get left out,even at more traditional schools. This is an excerpt from a book I have written on drawing and painting that addresses the problems of teaching abstract painting.http://martinmugar.blogspot.com/2012/01/humpty-dumpty-effectonce-veneer-of.html

Superb article! Thank you, Ms. Fendrich for your expert deconstruct of the Emperor's new clothes i.e. the prevailing trend of slick rhetoric (to the point of obsfucation e.g. the excerpt from MoMA's "Forever Now" exhib.) over basic painting principles and skill. It is a truthful and incisive piece, clearly coming from a deeply-caring artist and dedicated teacher. Painting, as we know, is a "practice" and, like any other practice, takes countless hours to become skilled and competent, and years to master. Particularly disturbing was the paragraph about "Even on the graduate level…some poorly trained students lack a basic understanding…" It made me feel extraordinarily grateful for my own outstanding teachers and training at MECA where it was instilled in us the only way to learn how to paint was to paint. It was all about "the process" (of seeing, and rendering what was perceived in that seeing) not about "making art"- (thank you by the way for making that distinction btw. "art" and "painting.") There's a reason that Cezanne was called the "Father of Modern Art" and why his paintings today remain so powerful, inscrutable, and enigmatic. He spent his life sitting in front of bowls of apples and Mt. St. Victoire, painting them over and over and over again. I revisit Cezanne often. His work, as well as that of Agnes Martin, are deep studies in meditation, ironically, where the "critical" mind is arrested and a deeper well of knowledge and intuition are engaged. Painting is hard, has been for centuries, and will continue to be. The part that made me sad- when you said some students felt cheated for not being taught the basics of painting- I thought, what a shame, as it is so deeply rewarding when one finally wrangles some order of clarity out of the mud of trial-and-error color-mixing. Your case for that was in the sentence- "And its felt composition within a rectangle offers models for understanding alternative ways to organize what happens on computer screens and cellphones." That's the beauty of it, we're not looking for quick answers only a click away, we are just giving ourselves over to the opening of "The Doors of Perception"- a fully present and engaged intensity of observation, like Cezanne and his apples.

Thank you again for your thoughtful, well-presented, and very necessary, article-

Barbara Hawes

hawesandart@gmail.com

this is an excellent article! Thank you!

Very good article and particularly poignant at this time when painting seems to have been moved into the closet of history. Can it be that the trials of learning this difficult craft are just far to exhaustive for contemporary minds? I would say emphatically no! At issue here is nothing different than the core desires of a degenerating corporate mentality which wiggled into our museums and galleries over the last 30 years or more, for simplistic and unchallenging art that requires little if any work to be done by a curator or gallery.

The fact that contemporary painting has been relegated to "fast food" intellectual jabber (as the author so aptly noted with example) and not adequately displayed in our museums, only accentuates the need for visual stimuli that does not require any real effort or an immersion in our craft. We seem to be in the period of the intellectualization of Duchamp's "Fountain" and its philosophical relevance to Corporatism!

Shame on two coats of paint for not publishing responses that were against this article, such as mine sent in last week. It would be better if you were more transparent about your biases.

Hi Anon,

I wasn't trying to control the debate–I'm not sure I got your comment. When I get anonymous ad hominem comments, though, I tend not to post them. Perhaps you can trying reposting it…?

Sharon @ Two Coats of Paint

The art is either so rigorous that it becomes poetry or so crazy that it creates its own logic. There may be another approach, but I've never seen an artist actually use one.

A successful art work is either so rigorous that it becomes poetry or so crazy that it creates its own logic. There may be another approach, but I've never seen an artist actually use one.

Thank you for writing this article. There is so much richness to the craft of painting and I constantly look for ways to strengthen my relationship with fundamental techniques so I have as many tools in my 'tool belt' as possible. Whatever painting tradition or technique, I am always amazed by the compounded knowledge of generations of painters passing down techniques, styles, and ways of visually responding through this medium.

I read this essay with great interest. I have been painting all my life but have no education at all. I gravitate between pride that I have boldly walked my own road and fear that I'm an ignorant fifth-rate schlepper, unworthy to even be considered an artist at all. The same terror has attended my career in animation…at first being accepted in a bohemian community but then feeling more and more isolated as the old-style individualists faded away and were replaced by people from expensive and exclusive art schools. I've learned whatever it is I've managed to know by imitating artists I like and listening to people's reactions to my work. As I've gotten older I've realized that time is the great arbiter and that even 'the great' can shrink to nothingness once the context that their work was created in fades into the past. From every genr� a few stand out who have the emotional and spiritual depth to transcend the harsh judgement of time. It would please me greatly to think that in 150 years someone will turn up on 'Antiques Road Show' with one of my paintings and the 'expert' will gush at this hidden treasure from a past age. To make something beautiful and compelling, however much or little technique is involved, should be the goal of a painter.

I've refrained from entering this fray because first, the writer is using critical thinking to supposedly criticize critical thinking. Secondly, the article seems to be more of a rant against the academic system than anything else.

The academic system certainly deserves its criticism, as well as the institution of art. However, if one has read Roland Barthes, both systems are only interested in producing products that will sustain the profit margin of the very rich. Critical thinking, on the other hand, is necessary to perhaps rise above, or remove oneself, from a system that doesn't care about much more than the exploitation of ideas and work. Everything is buyable. The purpose of everyone is to be exploited. Art produces commodities to be speculated upon, the same as gold or oil. Buy into it, and have ulcers wondering where your creativity went.

Mike

This is a very flawed article, filled with unsubstantiated opinion, conjecture, and anecdotal claims, not evidence, fact, or repeatable quantifiable data.

Excellent article. Hey, people responded. A lot of people.

Thank you for this article, Laurie Fendrich. As a painter and an adjunct professor of art, I've noticed this relentless push of language borrowed from sociology. I've had painting students and grad students feel increasingly beaten down as their attempts to develop by trial and error and exploration of the medium were seen as irrelevant (by the prevailing philosophy of the institution) – why develop a feel for paint when you could be handling big ideas in a post-studio practice? What's the use? This is the question that hunts and crushes exploration that isn't verbal.

Your article put words on something that I feel is a profound disservice to young painters. (and teachers who care about the mystery and uncertainty of the developing painting)

thank you again. m

Laurie Fendrich has exposed the farce that is apparent in many

of today's college studio art programs. Thankfully some people

who want to learn the craft of painting have become aware of

better options that are available to them such as the various

painting ateliers and stalwarts such as The Art Students League.

There is far too much written nonsense hung on painting today.

If I were asked to advise a young student about being an

art student in college I would advise as follows: Unless you

have a desire to work towards a tenure track college level

teaching position do not choose studio art as your major.

The only reason for obtaining an undergraduate art degree

is to be able to go for M.F.A. which is the pathway to hopefully

obtaining a tenure track college level teaching position.

These positions will become less available in the future

especially as many colleges continue to seek out adjuncts to teach studio courses especially the introductory classes. In my

opinion the heyday of having a good chance of landing

a tenure track position was the from the 1960's through the

mid 1980's. I would advise the individual to seek out

other routes to learn the craft of painting so that they will be able

to express themselves fully.

A few years ago a very good friend passed on. He taught

art at the college level for nearly 44 years. It was a state college but a few years ago added whatever was needed and now is a university. My friend though still wanted to teach the fundamental courses about oil painting as well as figure drawing/painting. He enjoyed the challenge of re tooling the courses each semester. He told me that he was not interested in teaching graduate courses offered through the MFA program because the other courses offered him more of a challenge. He enjoyed teaching the craft of painting and his students were very fortunate. He also taught a course on art philosophy. Unfortunately it seems that far too many colleges consider the fundamentals of painting to be out of date.

I had the wonderful opportunity of participating in a weekend workshop at The National Academy of Art, NYC with Wayne Thiebaud back in 1985. It was a pleasure to be able to study ,{even if only for 2 days}, with a painter's painter who knows both the how and why of painting. Also in the 1980's I attended a lecture by Robert Motherwell. Here was another artist who could talk about painting without the pretentious Art Forum nonsense. I was very fortunate to have studied with artists who while not well known knew what I needed to know in order for me to paint. I have an M.A. in Fine Arts. Painting. The state college, { now a university}, that I obtained my M.A. from did not offer an M.F.A. at that time. Again I was fortunate because professor who taught the majority of my studio courses helped me to think about not only the how but also the why of what I was doing. I still have my notes from the critiques that I still refer to.

Dear njart73- Thank you! I concur. This article prompted me, as well, to take the time to craft a response(7th down from the top, if care to read.)

And, again, my thanks to Laurie Fendrich for articulating what a lot of us painters have suspected all along, that it is not being instilled at (some of) the art schools the discipline required to master the skills of drawing and painting.

The pervasive challenge these days is the computer, where everything can be had "instantaneously."

My thanks to everyone who have "weighed in"-

Hawes & Art

This is an article about painting, not an article about science.

Artist should not be encouraged. We all have our problems and if someone wants to paint to help them cope, fine but do not tell me about it or even have me look to see if I can feel the pain, heart ache or even discomfort. I love pigment but no matter how an artist uses it (except my art) It has been done before and it will be done again.

Nice article but it is all to surreal because I know this article is about learning from it and the comforting delusions of making sense of the art being so easily produced and sold.

This article needed to be told, this article needs to be responded to but just like an artist that needs to paint, there is no end in the subject.

Unfortunately as a self taught artist that is an artist on my terms an ultimate artist, I have an idea. I would say a solution but all that mistaken themselves as me would severely object to my idea that is truly a solution. (Below is a partial idea, the solution is implied.)

When art has been done before even in the slightest it should not be considered art but a copy. If art is signed by the artist it is a copy. If an artist cannot make art that is so strong that it can be recognized on its merits then it is not art.

No matter how beautiful or large of scale or tiny of scale the “Art” is, it should be labeled “Crap”. If there has ever been anything even remotely similar done in the past as far as art is considered, It is a copy. I should say to the point that if the pigment on the canvas is flat or applied flat it is a copy.

Of course my art is so new and innovative that I cannot even use those terms because of the over use by sellers of art and curators that use this term because they would do anything to sell.

This is another subject; Curators and art dealers need to be called liars or frauds if they use the term “Mantra” or “metaphysical� or “essence of …”

The sad thing is this article is not about solutions it is about the need to be heard and have the intellectual concur.

Like most of us I have done my part in promoting this state of art by looking at a very young artist rendition of the �Essence� of a painting of her dog that died. I took my time and looked and looked at this very weak painting and finally turned to her and gave her an encouraging word. Now she is a successful artist and although her scale is larger and her color pallet has become more expensive she is oblivious to the waste she has produced and more importantly sold to the unsuspecting victims that they were mislead. (As art, not about being happy with their purchase)

Stop it! Artist should not be encouraged� at all. Unless, unless it is original. The subject should be �Is it original?� the subject should always be is it original. No one can stop an artist from painting but everyone should discourage them from torturing the unsuspecting masses of the artist�s and more importantly sellers� fraud.

There are no laws in art, though it appears that Amys rebutal, confirms the articles intentions,,,,,

I am with you Amy. I think that critical thinking is a necessary part of the painting process. The best painters I know are fairly balanced between their intuitive and analytic sensibilities.

Terrific article, Laurie!

Amen.

As a painter of both photo-realism and abstraction I find consciousness and the intellect play a superficial role in painting, and the more artists have used their intellect the worse the image, with the rare exception. Visual language uses the visual cortex, a different part of the brain than the intellect. My paintings reveal a complexity and beauty that is beyond what I can think of when I start, as I reach beyond my knowledge, I push to learn anew, seek new knowledge when I paint. Thinking, on the other hand, is limited to the known, thinking can only can only deal with already acquired knowledge.

Duchamp despised the optical and the artisanal and his influence has ruled the last century. Yet Duchamp made that choice to set his brand by rejecting the Impressionists. The optical requires skill and years of experience. The artisanal means a careful hand made object by a craftsman. Surely these are to be admired rather than despised? Duchamp’s intellect focus was meant to “destroy art”. He succeeded in destroying his own ability to make art; “it was like a broken leg, he said”. If you keep saying that making art and technique are meaningless, eventually you will believe your own words and lose the motivation for technique and making. Duchamp’s conceptual approach is now a ruling principle in the art world and responsible for the growing plague of boring exhibitions.

thank you

Teaching painting is about showing a student how to use the tools we know about and how to identify and break down personal rules or compulsions that bind the painter to a narrow path of facsimile, pandering, illusion and shtick. A teacher can only pass on what they know. Critical thinking should be a part of a growing artist’ mind set. Technique is always helpful. In rendering, learning to see color and translate it to canvas is throwing away what you think you know; detecting that a shadow in grass under a blue sky reflects some blue, it’s not just a darker green; or a foreshortened hand doesn’t really look like a hand. Then, with all that knowledge, consciously throw away whatever you want. If you need to sell art to pay bills, unfortunately you have to massage your audience by only throwing away what is popular to throw away. If you don’t need to sell paintings, you can follow your whims. You’re best work will be ignored and potential buyers will be really interested in your old work you did that abided by the rules and evokes traditional feelings about fancy museum paintings. Unfortunately, your audience, who has the money, wants art that says “I am a success, as you can see and this painting is the painting of a successful person.” If on the other hand, they have somehow mentally navigated as you have to enjoy your new work as you do, chances are they are as broke as you. Given time though, your work may become known by some subtle fortunate shtick or trick and some sales ensue. A brief wave, and you wonder if you have it in you again. Eventually, you just paint whatever you want because you don’t do it for money. That’s if you are a painter. The accumulation of years of learning, jabbering and persistence get tossed aside and one paints. Now try painting the ugliest painting possible, and you learn more than doing 100 careful compositions. Over and over til they become beautiful to you. Then begin again. Uglier yet. The fun part of painting is in setting up the canvas and laying down some strokes. The second it defines itself, you’ve turned the corner and you’re now working. Forget that none of the money is trickling down to you from the Minnesota flour and Wisconsin cheese magnates. Feel good your painting does not match any of their couches. Not because they are not good people, but because you are not trying to match a couch for money. It’s a form of prostitution if you really value art. If not, you’re a business person with a brush.

So the way this relates back to teaching art is this. Teaching and learning art is as subjective as art itself. It seems the discussion of whether art making can be taught has come to conclusions it cannot accept, which is no, it is self taught. The paradox is that a successful teacher has a student succeed by rebellion. It’s a magic trick. Sure, you can show a biology major how to paint a pair of shoes, but you can’t teach a painter how to ascend above the 10 billion mediocre paintings on the internet. Or how to get enough charisma to rub elbows with collectors and museum curators. Or what motivates someone to do so beyond ego, insecurity, revenge or general want for fame and self lust.

In the end, art should be fun. All the word-smithed rants about whether art can be taught… of course you must say yes to the student who is paying you to do so. In the end, a painting to the painter is meditative or miserable. To the rest it is sadly, a possession of value tied to the exotic bio of the painter.

To the romantics, I say have fun in your fantasy. Who knows where it might lead. But don’t give a care that your name gets into an art history book. In 100 years, nobody will know you. Your name is a string of letters. We don’t know Van Gogh, or what he was really. Just a name. Art has the attractiveness of immortality, that’s the catch. To think people are ewing and ahhing years after your dead is a fundamental weakness of the human mind. It only serves to motivate the artist to work when they know in their heart art beyond the enjoyment of creation is dead. Museums are not unlike funeral homes.

So critical thinking is bad for art so let us use critical thinking to think about how to not think critically about painting? This is like a little kid crying because they can’t play with the adult conversations. If you don’t enjoy it you don’t have to use it, if you don’t understand it, you are lazy.

Thank you, Ms Fendrich.

The emperor is naked, and you have pointed out his nakedness and laughed… It’s pretty awesome when the entire ivory-tower pomposity of the self-congratulatory critical contemporary art world is reduced to a dick joke. Considering one of the lofty aims of post-modernity was to destroy elitism in the fine arts, it is gratifying to have it so clearly stated that said elitism has simply been subverted into a sneering dismissal of the “academically visually illiterate”, and an elevation of overthinking to the pinnacle of artistic excellence. Love your work.

Look and put look and put look and put and after many, many, looks and puts may come invention, always remembering to start with a broom and finish with a noodle. If you can manage, once you know what you are doing, to find yourself in the free fall neutral gear, you may find yourself feeling deliriously happy (quietly within) when ‘good paint… happens’, and there is the reward, the natural high.

When I started art school, 51 years ago, we drew and drew, we learned what paint was made from, our training was, I guess you may say, academic, but it stood us in good stead. We were told to breath, sleep, live, art and allow ourselves to be as one with it. Following that credo, along the way I have enjoyed quite a few moments, of pure bliss. Now how do you teach that to others unless you are equally impassioned? We were told that art school was the beginning and that we should paint for about 15 years after finishing before we showed as it would take that long to hone our skills and find something worthwhile to say in our work and reflect our own way of seeing.

We were also encouraged to look at a work with our gut.

50 SECRETS OF MAGIC CRAFTSMANSHIP

Secret Number 50 is this: that when you have learned to draw and paint without mistakes, when you know how to distinguish the sympathies and the antipathies of natural things with your own eyes, when you have become a master in the art of washing and when by your own resources you are able to draw an ant with the reflections corresponding to each one of its minute legs, when you know how to practice habitually your slumber with a key and the so hypnotic one of the three sea peach eyes, when you have become a master in the resurrection of lost images of your adolescence, thanks to the natural magic of the retrospective use of your araneariums, when you have possessed the mastery and the most hidden virtues belonging to each of the colors and their relations to one another, when you have become a master in blending, when your science of drawing and of perspective has attained the plenitude of that of the masters of the Renaissance, when your pictures are painted with the golden wasp media which were then as yet unknown, when you know how to handle your golden section and your mathematical aspirations with the very lightness of your thought, and when you possess the most complete collection of the most unique curves, thanks to the Dalinian method of their instantaneous molding in dazzlingly white and perfect pentagons of plaster, etc. etc. etc., nothing of all this will yet be of much avail! For the last secret of this book is that before all else it is absolutely necessary that at the moment when you sit down before your easel to paint your picture, your “painter’s hand” be guided by an angel.

Salvador Dali, 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, Dover Publications, Inc., New York

It’s an excellent article Laurie Fendrich, and the link provides clarification for those less intimately familiar with “the white book.”

Thank you

Pingback: Willow Weep For Me… | David Manley - Artist

Pingback: A Critique | Abstract art in the era of global conceptualism

Many old, or ancient media are under threat from many corners. But, as they say of grapes (there are no bad ones), there are no exhausted media, though the products of any media can be (as with wines) not so interesting. It’s all part of the mystery of art, and I have to say that what might be needed more than anything is what was, in the ’70s, called open-ended discussion. Laurie has done that. As someone who has dealt curatorially over the decades with my share of conceptual practices, I’d say the surprising thing is that her ‘opening up of the field’, as it were, is (yet again) reclaiming the space that the mystery of painting should rightfully occupy. Paint can be informed by any ideas it wishes to pick up on. Her point is that it need/should not be in thrall to imposed concepts external to paint’s interior dynamic. That’s why paint is, and should be, so far from being dead, that it could be said to be entering its prepubescent phase only right about now. With any luck, we have many centuries of paint’s evolution to marvel in, but it will, of course, be for others to do the marveling. In one sense, what Laurie wrote is simply obvious to the open-ended mind.

To those who argued that the author was using critical thinking to critique itself…..to deconstruct critical thinking…well she isn’t. What she is specifically calling into question is the value of critical thinking and theory as applied to painting, as applied to a specific activity, and there is nothing illogical in that.

I , for one, completely agree with her.One way critical theory is sold to art students is that it is termed “art theory”; with the implication being that– as with all other practical disciplines–a knowledge of theory will aid the acquisition of the practical. An auto mechanic for example undoubtedly benefits from a theoretical knowledge of engines and how they work so therefore, thinks the art student, some knowledge of art theory will help me be a better artist.The problem here, however, is that what passes for art theory is not the same sort of practical information that passes for theory in a mechanics classroom.Actually what is taught under the rubric of “art theory” is not “theory” at all……rather it is a body of thought springing from anthropology and sociology that examines the various”meanings” a work of art can have.The idea being that once a student knows what he wants his painting TO MEAN then he will be able to paint his way to that goal.This is totally arse about face. Unlike an auto mechanic the erstwhile painter is not taught the mechanics of his trade, the properties of paint, etc, how to produce a certain effect on a canvas with pigment, etc; what he is taught is simply the meaning of spark plugs. No auto mechanic has become a better mechanic through knowing the meaning of spark plugs, what makes a mechanic better at his craft is knowledge of material properties.Painting is no different.Knowing the equivalent of the meaning of spark plugs does not make a student painter any better at his craft.Knowing what a painting might “mean” gives one absolutely no knowledge of how to get there.It just makes the student more verbally articulate during a critique.It would not be tolerated in an auto mechanic’s classroom so why is it tolerated at art school? Painters are in the business of creating meaning but the nature of that meaning is entirely up to consumer.Artists can’t control meaning…..but they can create

it.

Good article and great comments!

It seems not very nice to pick up on the last comment if you are in no way going to engage in the political angle it presents regarding painters as agents who operate according to generational and commercial transitions. It would be nicer to accept this and then perhaps go through the spellings with an open mind. Rigidity and fluency are not the same thing. Overall it’s an interesting thread.

I quite agree. Duchamp�s aim, taken from Dada was to destroy painting. Andy Warhol’s aim was simply to mock it. Irony (the expression of one’s meaning by using language that normally signifies the opposite, typically for humorous or emphatic effect) came to be seen as a essential aspect of Art post Warhol.

I agree painting is a visual language. You either get it or you don’t. You can either do it or you can’t.

Talent not to mention genius is in short supply.

Pingback: Cultivate Insouciance - Avoid Doubt - Ruth Armitage