Contributed by Jonathan Stevenson / Two new films concern edgy women of the New York art scene: Lisa Immordino Vreeland�s Peggy Guggenheim: Art Addict and Laurie Anderson’s Heart of a Dog, a moving meditation on dying and love. Vreeland builds a portrait of the visionary gallerist, proto-feminist, and renowned libertine as a social rebel and intuitive art savant around a series of taped interviews and an abundance of old footage. While that methodology makes it difficult to forge a character-plumbing film biography, it works well for marking Guggenheim�s prominent place in twentieth-century art history, and for framing her endearing eccentricities: at bottom a bit of a misanthrope, she is buried in Venice with 14 of her dogs (mainly lhasa apsos and shih-tzus).

Guggenheim�s even, unsentimental candor about her often dual role as patron and paramour invalidates any simple portrayal of her as a starry-eyed groupie and in fact suggests that her seduction of the likes of Max Ernst and Jackson Pollock might well have had their own tactical side. She may have slept around and felt as though she had fallen short as a mother, but she had genuine heart and an eye that was well ahead of its time � and, in particular, of her buttoned-down Uncle Solomon�s. He sneered at her offer of Kandinskys in the 1940s, only to amass for his museum decades later the largest collection of the abstract artist�s works in the United States, as well as exhibiting her collection there.

If Guggenheim�s sensibility ultimately gravitated uptown, Laurie Anderson�s has stayed downtown, with Lou Reed. Heart of a Dog is her avant-garde contemplation of life and death in the wake of his death in 2013. Penetratingly thoughtful and fiercely eclectic, it�s an existential stocktaking that burns dreamily from her surreal conjuring of giving birth to her own dog to Reed�s sage rendition of �Turning Time Around� as the credits roll, compiling meditations on 9/11, Tibetan Buddhism, and the surveillance state and searing biographical reminiscences. She links her empathy to a stay in the hospital for a broken back at age 12, when she saw burn victims, and her stoic determination to her mother�s singular moment of love towards her, when Anderson, as a girl, saved her twin brothers from drowning.

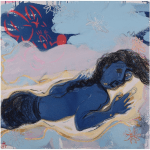

The eponymous dog is her rat terrier Lolabelle, who dies after Anderson finds herself unable to have her euthanized, and the film occasionally adopts the dog�s vulnerable, low-slung point of view. Anderson�s favorite painting, showcased in the movie, is The Dog, in which a small canine tremulously looks up at a lambent yellow sky, as though apprehending (she suggests earlier) 180 degrees of mortality previously unrecognized. Metaphorically, that basic arc expands for everyone as time goes on, and settling the earthly account means according its gifts and pains due consideration. Anderson must be thinking of Reed, to whom the film is dedicated, when she declares that the purpose of death is the release of love, of which this unique movie is strong evidence.

——

Two Coats of Paint is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To use content beyond the scope of this license, permission is required.